Most of the corporate whistleblower protection laws enforced by OSHA, including the Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower protection law, require the whistleblower to prove that the protected whistleblowing was a “contributing factor” in the employer’s decision to take an adverse employment action. What is “contributing factor” causation?

A contributing factor is “any factor which, alone or in connection with other factors, tends to affect in any way the outcome of the decision.” Powers v. Union Pacific Railroad Co., ARB No. 13-034, slip op. at 11, ALJ No. 2010-FRS-30, (ARB Mar. 20, 2015) (en banc). The standard originated under the Whistleblower Protection Act (“WPA”), which prohibits retaliation against federal employees. Before the WPA, a federal employee had to show that her protected disclosure “constituted a ‘significant’ or ‘motivating’ factor in the agency’s decision to take the personnel action.” Marano v. Dep’t of Justice, 2 F.3d 1137, 1140 (Fed. Cir. 1993) (citing Clark v. Dep’t of the Army, 997 F.2d 1466, 1469–70 (Fed. Cir. 1993)). But by enacting the WPA, Congress “substantially reduc[ed]” a whistleblower’s burden and sent “a strong, clear signal to whistleblowers that Congress intends that they be protected from any retaliation related to their whistleblowing.” Id. (citing 135 Cong. Rec. 5033 (1989) (Explanatory Statement on S. 20)). Congress intended specifically to overrule case law that required a whistleblower to prove that his protected conduct was a “significant,” “motivating,” “substantial,” or “predominant” factor in a personnel action in order to overturn that action. Id.

In light of the standard’s meaning, “[a] complainant need not show that protected activity was the only or most significant reason for the unfavorable personnel action, but rather may prevail by showing that the respondent’s reason, while true, is only one of the reasons for its conduct, and another [contributing] factor is the complainant’s protected’ activity.” Powers, ARB Case No. 13-034, slip op. at 11; see Blackie v. D. Pierce Transp., Inc., ARB Case No. 13-065, ALJ No. 2011-STA-055, 2014 WL 3385883, at *6 (June 17, 2014) (citing Araujo, 708 F.3d at 158); Marano, 2 F.3d at 1141 (AIR 21 complainant “need not demonstrate the existence of a retaliatory motive . . . [or] that the respondent’s reason for the unfavorable personnel action was pretext”); DeFrancesco v. Union R.R. Co., ARB Case No. 10-114, ALJ No. 2009-FRS-009, 2012 WL 694502, at *3 (Feb. 29, 2012) (“The ALJ concluded that DeFrancesco failed to show that his protected activity was a contributing factor because he did not prove that his employer was motivated by retaliatory animus. This is legal error.”); Zinn v. Am. Commercial Lines Inc., ARB Case No. 10-029, 2012 WL 1143309, at *7 (Mar. 28, 2012) (“The ALJ also erred to the extent he required that Zinn show ‘pretext’ to refute [respondent’s] showing of nondiscriminatory reasons for the actions taken against her.”); Warren v. Custom Organics, ARB Case No. 10-092, ALJ No. 2009-STA-030, 2012 WL 759335, at *5 (Feb. 29, 2012) (“Under the 2007 amendment to the STAA burden of proof, an employee is not required to prove that his employer’s reasons for an adverse action were pretext, e.g., that the employer had an alternate, albeit improper, motive for the adverse action, to prevail on a complaint.”); Klopfenstein v. PCC Flow Tech., Inc., ARB Case No. 04-149, ALJ No. 04-SOX-11, 2006 WL 3246904, at *13 (May 31, 2006) (citing Rachid v. Jack in the Box, Inc., 376 F.3d 305, 312 (5th Cir. 2004)) (“[A] complainant is not required to prove pretext.”). Likewise, an employee need not prove retaliatory motive to make his contributing factor showing. See Powers, ARB Case No. 13-034, slip op. at 19–20, 28. In Powers, the ALJ concluded that the employee failed to make his contributing factor showing. The ALJ committed reversible error in reaching this determination because he credited and relied on testimony from the employers’ witnesses that they acted on non-retaliatory motives. Id. at 28.

A complainant may establish that the protected activity was a contributing factor by direct or circumstantial evidence. Circumstantial evidence may include

- temporal proximity;

- pretext;

- inconsistent application of an employer’s policies;

- an employer’s shifting explanations for its actions;

- antagonism or hostility toward a complainant’s protected activity;

- the falsity of an employer’s explanation for the adverse action taken; and

- a change in the employer’s attitude toward the complainant after he or she engages in protected activity.

Lancaster v. Norfolk S. Ry. Co., ARB No. 2019–0048, ALJ No. 2018–FRS–00032, slip op. at 7 (ARB Feb. 25, 2021); Bechtel v. Competitive Tech., Inc., ARB No. 09–052, ALJ No. 2005–SOX–033, slip op. at 12 (ARB Sept. 30, 2011).

In sum, the burden to prove causation in a SOX whistleblower case is not onerous. Indeed, temporal proximity alone can be sufficient proof in certain cases.

On December 2, 2022, the Sixth Circuit held that

As noted earlier, a contributing factor is one which “alone or in connection with other factors, tends to affect in any way the outcome of the decision.” Consol. Rail Corp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Lab., 567 F. App’x 334, 338 (6th Cir. 2014) (emphasis added) (quoting Araujo v. New Jersey Transit Rail Operations, Inc., 708 F.3d 152, 158 (3d Cir. 2013)). NSRC argues for a different standard—that Lancaster must additionally prove “intentional retaliation prompted by the employee engaging in protected activity,” and he failed to do so here. Dakota, Minn. & E. R.R. Corp. v. U.S. Dep’t of Lab., 948 F.3d 940, 942 (8th Cir. 2020)(quoting Kuduk v. BNSF Ry. Co., 768 F.3d 786, 791 (8th Cir. 2014)). This misapprehends the correct legal standard. “A prima facie case does not require that the employee conclusively demonstrate the employer’s motive.” Kuduk, 768 F.3d at 790 (alteration in original) (quoting Coppinger-Martin v. Solis, 627 F.3d 745, 750 (9th Cir. 2010)); see also Lockheed Martin Corp. v. Admin. Rev. Bd., 717 F.3d 1121, 1137 (10th Cir. 2013). Rather, as our sister circuits have explained, “the employee need only make `a prima facie showing that protected behavior or conduct was a contributing factor in the unfavorable personnel action alleged in the complaint.'” Coppinger-Martin, 627 F.3d at 750 (quoting 29 C.F.R. § 1980.104(b)); see also Kuduk, 768 F.3d at 791; Consol. Rail Corp., 567 F. App’x at 338; Ameristar Airways, Inc. v. U.S. Dep’t of Lab., 650 F.3d 562, 569-70 (5th Cir. 2011).

Norfolk Southern Railway Company v. United States Dep’t of Labor, 21-3359 (6th Cir. Dec. 2, 2022).

A whistleblower’s ongoing litigation against the respondent can establish causation. In March v. Metro-North Commuter Railroad Co., ARB No. 2021-0059, ALJ Nos. 2019-FRS-00032, -00035 (ARB Jan. 21, 2022) (per curiam), the ARB found that there was a substantial basis for the ALJ “to reasonably conclude [that complainant’s] ongoing litigation against the company: 1) remained a persistent presence in the minds of the actors in this case; 2) had ongoing ramifications for March; and 3) helped shape how events unfolded.” Slip op. at 12. The ARB noted that this analysis was consistent with its decision in Brucker v. BNSF Railway Co., ARB No. 2014-0071, ALJ No. 2013-FRS-00070, slip op. at 12 (ARB July 29, 2016), in which the ARB stated: “Ongoing litigation kept the protected activity ‘fresh as the events in the case unfolded’ and led to ‘continuing fallout’ for the complainant.” Id. (quoting Carter v. BNSF Ry. Co., ARB Nos. 2014-0089, 2015-0016, -0022, ALJ No. 2013-FRS-00082, slip op. at 4 (ARB June 21, 2016)).

Where the whistleblower has plausibly alleged that the standard of conduct applied to them was different from the standard applied to comparators, the whistleblower has sufficiently pled causation (there is an inference that the defendant’s proffered reason for his termination was pretextual): “All the alleged comparators allegedly engaged in conduct comparable to the plaintiff’s conduct – if not more culpable conduct – and all were indicted for or pleaded guilty to spoofing, unlike the plaintiff. Given that the defendant purportedly terminated the plaintiff for the appearance of misconduct, it is unclear why the same rationale should not have applied to the comparators. Yet, the defendants kept the comparators employed long after there were significant issues regarding the appearance of misconduct. On this basis, the plaintiff has alleged sufficiently that the standard of conduct applied to the plaintiff was different from the standard applied to the comparators. See Ashmore v. CGI Group, Inc., 138 F. Supp. 3d 329, 347 (S.D.N.Y. 2015) (“The record is devoid of evidence definitely demonstrating that employees similarly situated to Plaintiff are routinely fired for comparable performance deficiencies or that Plaintiff’s conduct contravened a rule customarily leading to immediate termination.”).” Turnbull v. JPMorgan Chase & Co., 2022 WL 10167580 (SDNY Oct. 17, 2022).

Zuckerman Law Amicus Curiae Brief Filed on Behalf of Senator Wyden and Representative Speier Clarifying the Contributing Factor Causation Standard

In July 2021, whistleblower protection law firm Zuckerman Law filed this amicus curiae brief in the Second Circuit concerning the appropriate causation standard under federal whistleblower protection laws.

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF OF SENATOR RON WYDEN AND REPRESENTATIVE JACKIE SPEIER AND IN SUPPORT OF THE PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE-CROSS-APPELLANTSOX Whistleblower Retaliation

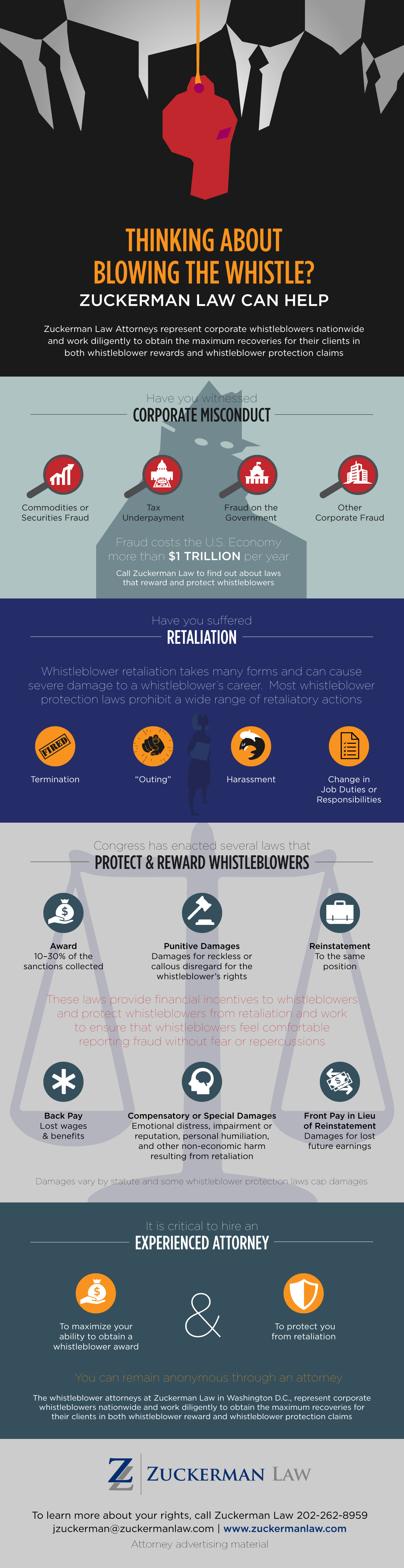

The experienced and effective Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower protection lawyers at Zuckerman Law have extensive experience representing corporate whistleblowers. U.S. News and Best Lawyers® have named Zuckerman Law a Tier 1 firm in Litigation – Labor and Employment in the Washington DC metropolitan area in the 2020 edition of “Best Law Firms.”

In 2019, the National Law Review awarded Zuckerman its “Go-To Thought Leadership Award” for his analysis of developments in whistleblower law. We represent whistleblowers nationwide.

To learn more about whistleblower rights and protections, contact Zuckerman Law at 202-262-8959.

Under the FRSA, a complainant must prove “as a fact and by a preponderance of the

evidence” that protected activity was a contributing factor in the unfavorable personnel action taken

by the employer. Palmer v. Canadian Nat’l Railway, ARB No. 16–035, ALJ No. 2014–FRS–154, slip op.

at 16 (ARB Sept. 30, 2016) (reissued with full dissent Jan. 4, 2017). A “contributing factor” is “any

factor which, alone or in connection with other factors, tends to affect in any way the outcome of

the decision.” Williams v. Domino’s Pizza, ARB No. 09–092, ALJ No. 2008–STA–052, slip op. at 6

(ARB Jan. 31, 2011); see also Frost v. BNSF Ry. Co., 914 F.3d 1189, 1195 (9th Cir. 2019). The ARB has

emphasized that the standard is low and “broad and forgiving”: The protected activity need only

play some role, and even an “[in]significant” or “[in]substantial” role suffices. Palmer, ARB No. 16–

035, slip op. at 53 (citations omitted); see also Rookaird, 908 F.3d at 461 (contributing factors “may be

quite modest—they include any factor which tends to affect in any way the outcome of the

decision.”) (cleaned up).

Complainant need not conclusively prove retaliatory motive or animus; “the only proof of

discriminatory intent that a plaintiff is required to show is that his or her protected activity was a

“contributing factor” in the resulting adverse employment action.” See Frost, 914 F.3d at 1195.The

Ninth Circuit has held that “by proving that an employee’s protected activity contributed in some

way to the employer’s adverse conduct, the [whistleblower] has proven than an employer acted with

some level of retaliatory intent.” Id. at 1196. There is no requirement that a plaintiff make any

additional showing of discriminatory intent. Id. (emphasis added). Contra, Murray v. UBS Securities, LLC, 43 F.4th 254, 259 (2nd Cir. 2022); Armstrong v. BNSF Ry. Co., 880 F.3d

377 (7th Cir. 2018); Kuduk v. BNSF Ry. Co., 768 F.3d 786, 792 (8th Cir. 2014); see also Koziara v. BNSF Ry. Co.,

840 F.3d 873 (7th Cir. 2016).

The ALJ must be persuaded that it is more likely than not that the protected activity played

any role in the adverse action, and the ALJ may consider any relevant, admissible evidence in making

this determination. Palmer, ARB No. 16–035, slip op. at 17–18, 52. The ALJ may consider

circumstantial evidence, including temporal proximity, shifting explanations for Respondent’s

actions, antagonism or hostility towards the complainant’s protected activity, the falsity of

Respondent’s explanation for the adverse action taken, or a change in Respondent’s attitude towards

Complainant after he engaged in protected activity. Lancaster v. Norfolk S. Ry. Co., ARB No. 2019–

0048, ALJ No. 2018–FRS–00032, slip op. at 7 (ARB Feb. 25, 2021).

Complainant’s burden of proving contributory causation will be met upon this minimal

showing even if the employer also had a legitimate reason for the unfavorable employment action

against the employee. Rudolph v. National Railroad Passenger Corp., ARB No. 11–037, ALJ No. 2009–

FRS–15, slip op. at p. 16 (ARB Mar. 13, 2013); Franchini v. Argonne Nat’l Lab., ARB No. 11–006, ALJ

No. 2009–ERA–014, slip op. at 9, 11 (ARB Sept. 26, 2012); see also Frost, 914 F.3d at 1196 (it is

possible for an employee to show retaliation even if the respondent had an honestly–held, justified

belief that the employee committed a violation for which he was disciplined.). Courts, however, “do

not sit as super–personnel departments picking apart Respondent’s business judgment.” Kuduk, 768

F.3d at 792. “An employer’s actions can be harsh, faulty, and unjustified, but this does not establish

that the employer retaliated for FRSA whistleblowing activity.” Acosta v. Union Pac. R.R. Co., ARB

No. 2018–0020, ALJ No. 2016–FRS–00082, slip op. at 11 (ARB Jan. 22, 2020).