In a False Claims Act case in which the relators allege that Mount Sinai Hospital and affiliated entities committed improper billing and wrongful payment retention misconduct, Judge Berman of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York held that the realtors could use confidential patient records as the basis for their qui tam action. The decision is available here.

In a motion to dismiss, the defendants asserted that the relators “may not rely on improperly obtained confidential patient records as the basis for their complaint.” Judge Berman rejected defendant’s request for preclusion of the patient records, holding that

there is strong public policy in favor of protecting those who report fraud against the government. See U.S. ex rel. Ruhe v. Masimo Corp., 929 F. Supp. 2d 1033, 1039 (C.D. Cal. 2012) (where relators “sought to expose a fraud against the government and limited [obtaining] documents relevant to the alleged fraud … this taking and publication was not wrongful, even in light of nondisclosure agreements, given ‘the strong public policy in favor of protecting whistleblowers who report fraud against the government.”‘) (citing U.S. ex rel. Grandeau v. Cancer Treatment Ctrs. of Am., 350 F. Supp. 2d 765, 773 (N.D. Ill. 2004) (“Relator and the government argue that the confidentiality agreement cannot trump the FCA’s strong policy of protecting whistleblowers who report fraud against the government.”)).

Judge Berman also noted the relators’ contention that HIPPA “carves out an exception that allows ‘whistleblowers’ to reveal such information to governmental authorities and private counsel, provided that they have a good faith belief their employer engaged in unlawful conduct.” The relators are represented by McInnis Law.

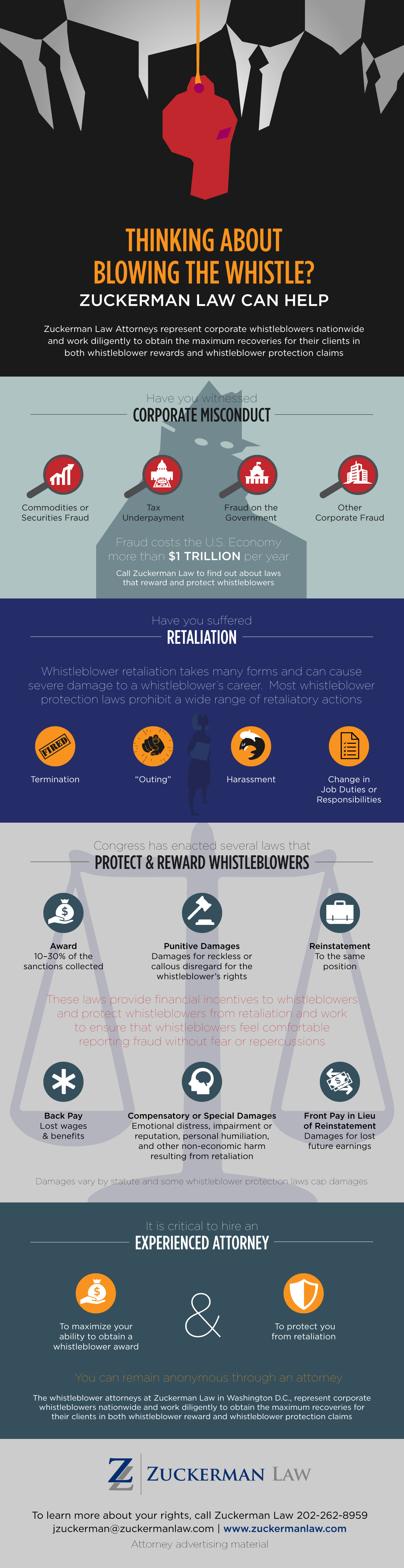

As Medicare fraud is estimated to cost taxpayers $60 billion to $90 billion each year, it is critical that the courts do not permit health care providers to use confidentiality agreements to immunize themselves from FCA liability. If confidentiality agreements were deemed to trump the FCA, then the government would lose its most effective tool in combatting health care fraud.

Nevertheless, whistleblowers should seek counsel before using confidential information to bring a whistleblower claim. And whistleblowers should avoid gathering evidence unlawfully and consider taking appropriate measures to protect certain confidential information, such as filing a redacted complaint that does not disclose patient names.

See these related posts and FAQs:

- Court Rules that Whistleblowers Can Use Confidential Company Documents to Expose Fraud

- Retaliatory Lawsuit Against Whistleblower Dismissed on Summary Judgment

- De Facto Gag Clauses: The Legality of Employment Agreements That Undermine Dodd-Frank’s Whistleblower Provisions

- 5 Questions To Ask Before Suing Over Whistleblower Theft

- Forbes Quotes Whistleblower Attorney Jason Zuckerman About Self-Help Discovery in Whistleblower Litigation

- Can Whistleblowers Disclose Secret Recordings to the SEC?

- Is a lawsuit against a whistleblower actionable retaliation?

False Claims Act Whistleblower Protection

To learn more about False Claims Act whistleblower protection, see our answers to frequently asked questions about the False Claims Act whistleblower protection law and see our recent article:

False Claims Act Whistleblower Protection LawClick here to learn more about damages or remedies in whistleblower retaliation cases and tips for maximizing your recovery.

As discussed by Judge Thrash in United States of America ex rel. et al v. ERMI, LLC, No. 1:20-CV-4181 (N.D. Ga. Nov. 2, 2023), when an FCA defendant’s breach of confidentiality agreement counterclaim only involves the failure to return evidence that is material to the relator’s FCA claim, that counterclaim is usually prohibited by public policy:

As a general matter, “[i]n the absence of an expression of Congressional intent to the contrary, a private agreement is unenforceable on grounds of public policy if its enforcement is clearly outweighed by a public policy against such terms.” Head, 668 F. Supp. 2d at 152. While there appears to be no binding precedent on this specific issue, there are several cases that provide guidance as to when a counterclaim for breach of a confidentiality agreement may be raised against a relator in an FCA case. When an FCA defendant’s breach of confidentiality agreement counterclaim only involves the failure to return evidence that is material to the relator’s FCA claim, that counterclaim is prohibited by public policy. Id.; United States ex rel. Grandeau v. Cancer Treatment Ctrs. of America, 350 F. Supp. 2d 765, 773 (N.D. Ill. 2004) (agreeing that a “confidentiality agreement cannot trump the FCA’s strong policy of protecting whistleblowers who report fraud against the government.”). If, however, the relator goes beyond what is reasonable to pursue their qui tam claim in maintaining and disclosing such information, that will constitute a permissible counterclaim. United States ex rel. Ruscher v. Omnicare, Inc., 2015 WL 4389589, at *5 (S.D. Tex. July 15, 2015); Walsh v. Amerisource Bergen Corp., 2014 WL 2738215, at *7 (E.D. Pa. June 17, 2014); see also Cafasso ex rel. United States v. Gen. Dynamics C4 Sys., Inc., 637 F.3d 1047, 1062 (9th Cir. 2011) (stating that if a public policy exception exists in these circumstances, “those asserting its protection would need to justify why removal of the documents was reasonably necessary to pursue an FCA claim”).

This dichotomy makes sense in light of the case law discussed supra, in subsection A., regarding independent damages. If a counterclaim for breach of a confidentiality agreement is challenging the retention or dissemination of information unrelated to the FCA case, then it will in no way resemble a disguised claim for indemnification or contribution. Furthermore, permitting a counterclaim for retention and dissemination of documents not reasonably related to the FCA claims will not leave whistleblowers unprotected. Information unrelated to the relator’s FCA claims will not be needed to comply with 31 U.S.C. § 3730(b)(2) or to meet the Rule 9(b) pleading standards. Additionally, since a counterclaim cannot be raised involving the retention of anything reasonably related to the FCA action, innocent relators will not be punished. Cf. Miller, 505 F. Supp. 2d at 28.

Judge Thrash granted the relator’s motion to dismiss the breach of fiduciary duty claim:

Cooley maintains that public policy prohibits ERMI’s breach of fiduciary duty claim from proceeding because permitting such a counterclaim would discourage whistleblowers from coming forward and thereby undermine the FCA. (Id. at 4-6). Several cases have held that at least some counterclaims are barred by the FCA under this public policy rationale. See, e.g., Mortgs., Inc. v. U.S. Dist. Court for Dist. Of Nev. (Las Vegas), 934 F.2d 209 (9th Cir. 1990); United States ex rel. Vainer v. DaVita, Inc., 2013 WL 1342431, at *4 (N.D. Ga. Feb. 13, 2013); United States ex rel. Rodriquez v. Wkly. Publ’ns, 74 F. Supp. 763 (S.D.N.Y. 1947). ERMI belittles this public policy rule as “judge-invented” and points to the fact that the Eleventh Circuit has not actually decided this issue. (Def.’s Br. in Opp’n to Mot. to Dismiss, at 5-6).

While ERMI is correct that the Eleventh Circuit’s reference to this rule was mere dicta, Israel Discount Bank Ltd. v. Entin, 951 F.2d 311, 315 n. 9 (11th Cir. 1992), “[t]he unavailability of contribution and indemnification for a defendant under the False Claims Act now seems beyond peradventure.” United States ex rel. Miller v. Bill Harbert Intern. Const. Inc., 505 F. Supp. 2d 20, 26 (D.D.C. 2007) (compiling cases) (“Miller“). Moreover, “there can be no right to assert state law counterclaims that, if prevailed on, would end in the same result” as an indemnification or contribution counterclaim. Mortgs., Inc., 934 F.2d at 214. On the other hand, a qui tam defendant can bring counterclaims if they are based on “independent damages.” United States ex rel. Head v. Kane Co., 668 F. Supp. 2d 146, 153 (D.D.C. 2009) (“Head“). In fact, it would violate procedural due process to dismiss a defendant’s compulsory counterclaim based on independent damages. United States ex rel. Madden v. Gen. Dynamics Corp., 4 F.3d 827, 830-31 (9th Cir. 1993). There are two types of counterclaims that are based on independent damages: (1) counterclaims in which “the conduct at issue is distinct from the conduct underlying the FCA case” and (2) counterclaims in which “the defendant§s claim, though bound up in the facts of the FCA case, can only prevail if the defendant is found not liable in the FCA case.” Head, 668 F. Supp. 2d at 153 (citation omitted). While nothing in the breach of fiduciary duty counterclaim limits its success to a finding of nonliability for Cooley’s FCA claim, the Court finds that ERMI’s claim falls, at least in part, in the first category.

A counterclaim will fall under the first category “if none of the elements of [the counterclaim’s] caus[e] of action implicate Defendant§s liability under the FCA.” Id. at 154. For example, a counterclaim asserting a breach of a non-disparagement provision was allowed to proceed because liability for that counterclaim depended on whether the relator “made disparaging or critical statements to third parties in violation of his contractual obligations after this suit was filed and completely apart from this proceeding.” Id. at 153. By contrast, the same court dismissed a claim for contractual indemnification even assuming there had been willful misconduct and a breach of contract because it was attempting to shift liability for the FCA violations to the relator. Id. at 154.

ERMI’s claim for breach of fiduciary duty relies on three alleged wrongful acts: (1) leading ERMI to believe that it was receiving legal advice from her, (2) relaying incorrect information about how the AHCA renewal process was going, and (3) becoming a relator in this action regarding the AHCA licensure. (Countercls. ¶¶ 31-33). Going in reverse order, the third allegation expressly relies on Cooley bringing this lawsuit as a relator and is therefore not distinct from Cooley’s claims. The second allegation does the same, albeit in a more subtle way. The FCA claims remaining in Cooley’s Third Amended Complaint deal mostly with ERMI’s activity in Florida either without a license issued by AHCA or based on a license obtained because of intentional misrepresentations made on AHCA license applications. (Third Am. Compl. ¶¶ 442-92). Claiming that Cooley should have to pay ERMI because her actions caused this problem and cost ERMI money is nothing more than a dressed-up (but still barred) claim for contribution or indemnification.

This leaves the allegation that Cooley was misleading ERMI into thinking she was providing legal advice. By contrast to the other allegations, this involves conduct that is entirely separate from Cooley’s FCA claim. ERMI alleges that Cooley was “continually providing interpretation and analysis of laws and regulations.” (Countercls. ¶ 31). The legal advice Cooley “repeatedly provided ERMI” is alleged to include “(a) regulatory compliance; (b) corporate formation and conversion; (c) litigation strategy; (e) intellectual property due diligence; and (f) other similar matters.” (Id. ¶ 14). This qualifies as an independent ground for damages. Whether Cooley breached her fiduciary duty by improperly giving legal advice on issues such as corporate formation is not going to stand or fall based on the result of Cooley’s FCA claims. As such, the breach of fiduciary duty counterclaim is not void for public policy reasons.[3]

Yet, Cooley also argues that ERMI has failed to allege facts showing how it was harmed. (Reply Br. in Supp. of Mot. to Dismiss, at 5-6). In its counterclaims, ERMI alleges that “[a]s a direct and proximate result of Cooley’s breaches of her fiduciary duty to ERMI, ERMI was harmed” and “is entitled to an award of compensatory damages in an amount to be proven at trial.” (Countercls. ¶¶ 34-35). Relying on Desai v. Tire Kingdom, Inc., 944 F. Supp. 876 (M.D. Fla. 1996), ERMI asserts that it is not required to “spel[l] out the exact damages it contends it is entitled to.” (Def.’s Br. in Opp’n to Mot. to Dismiss, at 9). While ERMI is correct that it need not comply with the heightened pleading requirements of Rule 9(b), “an allegation that defendant `suffered damages’ without particular facts as to how she was damaged does not satisfy Twombly and Iqbal.” Int’l Bus. Machs. Corp. v. Dale, 2011 WL 4012399, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 9, 2011) (citation omitted). ERMI only provides specific facts showing damages related to the failure to renew the AHCA license. However, for the reasons described above, that amounts to a claim for contribution or indemnification and cannot proceed.

Additionally, ERMI’s reliance on Desai is misplaced. That case involved an Americans with Disabilities Act claim and a similar state law claim; both of which required the plaintiff to show that his injury substantially limited his ability to, e.g., walk, work, or perform manual tasks. Desai, 944 F. Supp. at 879. The court there rejected a challenge that the plaintiff failed to state a claim by not specifically alleging his knee injury impaired his abilities to do those tasks. Id. The court found that such an allegation could be inferred from other specific facts the plaintiff alleged, such as being told his injury was permanent, needing to reduce his working hours, being forced to give up tennis and jogging, and experiencing great pain and being unable to bend his leg after a twelve-hour shift. Id. By contrast, the Court cannot infer any independent damages from ERMI’s specific allegations. As a result, ERMI has failed to properly state its breach of fiduciary duty counterclaim. The Court will dismiss this count without prejudice to provide ERMI with the opportunity to restate its allegations.

False Claims Act Whistleblower Protection Lawyers

The experienced whistleblower lawyers at Zuckerman Law have represented whistleblowers under the qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act and under other whistleblower reward and whistleblower protection laws. To schedule a free preliminary consultation, click here or call us at 202-262-8959.