Overview of SOX Whistleblower Protection from Experienced SOX Whistleblower Lawyers

Whistleblower retaliation takes a terrible toll on the courageous whistleblowers that speak up about fraud or other unlawful conduct in the workplace. Corporate whistleblowers often suffer reputational harm, alienation, emotional distress and diminished career prospects. Fortunately, the Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower protection law provides robust protection for corporate whistleblowers.

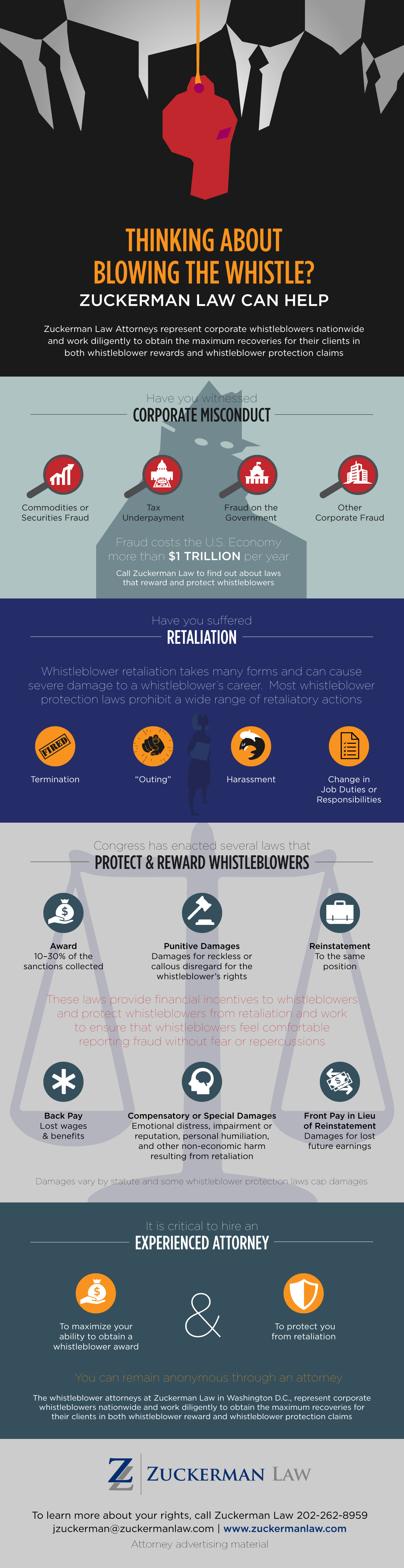

Leading whistleblower firm Zuckerman Law represents senior professionals in high-stakes employment matters, including corporate officers, executives, managers, and partners at professional services firms. Click here to read testimonials from CEOs, CFOs, and other senior professionals that we have represented. For a free initial consultation, call us at 202-262-8959 or click here.

For more information about protections and remedies for corporate whistleblowers, download our free guide Sarbanes-Oxley Whistleblower Protection: Robust Protection for Corporate Whistleblowers.

The whistleblower protection provision of SOX protects:

- employees, officers and agents of publicly traded companies (companies issuing securities registered under section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 or required to file reports under section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934);

- employees of any subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly-traded company whose financial information is included in the consolidated financial statements of such company;

- employees of contractors or subcontractors of public companies, including the attorneys and accountants who prepare public companies’ SEC filings;[5] and

- employees of nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (as defined in section 3(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78c).

There are, however, some limitations on SOX coverage for employees of contractors of publicly traded companies:

- “Contractor” is limited to business relationships where “performance of a contract will take place over a significant period of time.”

- SOX “protects contractor employees only to the extent that their whistleblowing relates to ‘the contractor ... fulfilling its role as a contractor for the public company, not the contractor in some other capacity.’” In other words, SOX protects a contractor employee who is in a position to detect and report securities violations — for example, the lawyers and accountants in the Enron scandal who were either directly or indirectly witness to the fraud.

- SOX does not cover contractor employees who experience retaliation that is unrelated to the provision of services to a public company. [6] A contractor’s fraudulent practices do not become subject to § 1514A merely because that company incidentally has a contract with a public company.[7]

To prevail, a SOX whistleblower must prove by a preponderance of the evidence that:

- they engaged in protected activity (they made a protected disclosure under Section 806);

- the employer knew that they engaged in the protected activity;

- they suffered an unfavorable personnel action;

- the protected activity was a contributing factor in the unfavorable action.[8]

Once a SOX whistleblower has proven these elements by a preponderance of the evidence, the burden is on the employer to prove by clear and convincing evidence that it would have taken the same adverse action in the absence of the employee engaging in protected activity.

Yes, a whistleblower can bring a retaliation claim under SOX against individuals who have the functional ability to retaliate against the whistleblower, and are aware of the whistleblower’s protected conduct (or influenced by a person with knowledge of the protected conduct).

The Fourth Circuit and a California district court have held that directors may be held individually liable under SOX as agents of a publicly traded company. See Jones v. Southpeak Interactive Corp. of Delaware, 777 F.3d 658, 675 (4th Cir.2015); Wadler v. Bio-Rad Labs, Inc., No. 15-cv-02356-JCS, 2015 WL 6438670 (N.D. Cal. Oct. 23, 2015).

The first showing that a corporate whistleblower must make to receive protection under SOX is that he engaged in protected whistleblowing, also known as protected conduct or protected activity.

Whistleblowers are protected under SOX for providing information, causing information to be provided, or otherwise assisting in an investigation regarding any conduct disclosing conduct that they reasonably believe violates:

- federal criminal prohibitions against securities fraud, bank fraud mail fraud, or wire fraud;

- any rule or regulation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”); or

- any provision of federal law relating to fraud against shareholders

when the information or assistance is provided to or the investigation is conducted by:

- a federal regulatory or law enforcement agency;

- any Member of Congress or any committee of Congress; or

- a person with supervisory authority over the employee (or such other person working for the employer who has the authority to investigate, discover, or terminate misconduct).

Significantly, SOX protects internal disclosures, such as an employee raising a concern to a supervisor about misleading financial data in a SEC filing.

SOX also prohibits retaliation for filing, causing to be filed, or otherwise assisting in a proceeding filed or about to be filed relating to:

- federal criminal prohibitions against securities fraud, bank fraud mail fraud, or wire fraud;

- any rule or regulation of the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”); or

- any provision of federal law relating to fraud against shareholders.

A SOX retaliation plaintiff need not demonstrate that they disclosed an actual violation of securities law; only that they reasonably believed that their employer was defrauding shareholders or violating an SEC rule.[9] Indeed, a reasonable but mistaken belief is protected under SOX. “To demonstrate that a plaintiff engaged in a protected activity, a plaintiff must show that [s]he had both a subjective belief and an objectively reasonable belief that the conduct [s]he complained of constituted a violation of relevant law.”[10]

Requiring a SOX complainant to demonstrate that they disclosed an actual violation is contrary to Congressional intent in that the legislative history of Section 806 specifically states that the reasonableness test “is intended to include all good faith and reasonable reporting of fraud, and there should be no presumption that reporting is otherwise, absent specific evidence.”[11]

No. A complainant need not allege or prove shareholder fraud to receive SOX’s protection. SOX was enacted to address “corporate fraud generally,” and so a reasonable belief that a violation of “any rule or regulation of the Securities and Exchange Commission” could lead to fraud is protected, even if the violation itself is not fraudulent. For example, SOX protects a disclosure about deficient internal controls over financial reporting, even though there is no allegation of actual fraud.[12]

As the Third Circuit held, SOX is meant to “protect people who have the courage to stand against institutional pressures and say plainly, ‘what you are doing here is wrong’ . . . in the particular way identified in the statue at issue.”[13] An employee has fulfilled that purpose if they disclose conduct that is within the “ample bounds” of the anti-fraud statutes. Such an employee is therefore protected even if they lacked “access to information sufficient to form an objectively reasonable belief” as to the specific elements of fraud. And they are similarly protected even if their belief is “reasonable but mistaken.”

Yes. Complaints about potential securities law violations may be protected under the whistleblower-protection provision of SOX. “A whistleblower complaint concerning a violation about to be committed is protected as long as the employee believes that the violation is likely to happen. Such a belief must be grounded in facts known to the employee, but the employee need not wait until a law has actually been broken to safely register his or her concern.”[14]

As a New York federal judge recently pointed out, limiting SOX whistleblower protection to disclosures of actual fraud “would lead to absurd results” by encouraging an employee to delay blowing the whistle until a potential violation has ripened to an actual violation.[15] Section 806 was “designed to encourage insiders to come forward without fear of retribution,” and therefore “[i]t would frustrate the purpose of Sarbanes-Oxley to require an employee, who knows that a violation is imminent, to wait for the actual violation to occur when an earlier report possibly could have prevented it.”[16]

To be protected under SOX, an employee’s report “need not ‘definitively and specifically’ relate to one of the listed categories of fraud or securities violations in § 1514A.”[17]

Whistleblowers are protected if they show that they reasonably believed that the conduct they complained of violated one of the enumerated violations in Section 806. Whistleblowers are not required, however, to tell management or the authorities why their beliefs are reasonable. Nor must their disclosures allege, prove, or approximate the elements of fraud.

All that SOX requires an employee to do is prove that they “reasonably believed” that their employer violated or is about to violate federal law.[18] The focus here is “on the plaintiff’s state of mind rather than on the defendant’s conduct.”[19] This rule is informed by the court’s recognition that, because “[m]any employees are unlikely to be trained to recognize legally actionable conduct by their employers,” an employee’s “belief” in their employer’s wrongdoing is “central” to the analysis of SOX-protected conduct.[20]

A Sixth Circuit opinion in a SOX case demonstrates the importance of broadly construing SOX-protected conduct. In Rhinehimer v. U.S. Bancorp Investments, Inc,.[21] the plaintiff Michael Rhinehimer alerted one of his superiors to unsuitable trades that a coworker made to the detriment of an elderly client. In response, Mr. Rhinehimer’s manager gave him a written warning. The manager admitted that the warning was motivated by the fact that Mr. Rhinehimer’s complaint “prompted a FINRA investigation . . . and anybody associated with this was really feeling the heat.” According to Mr. Rhinehimer, the manager then admonished Mr. Rhinehimer that if he sued the bank, then his career in the city would be over. U.S. Bancorp Investments (“USBII”) placed Mr. Rhinehimer on a performance-improvement plan requiring him to increase his monthly revenue to $40,000. Shortly thereafter, the bank fired him.

At trial, a jury found that USBII disciplined and fired Mr. Rhinehimer in deliberate retaliation for raising his concerns about the unsuitable trades. On appeal, USBII argued, that Mr. Rhinehimer was required to establish facts from which a reasonable person could infer each of the elements of an unsuitability-fraud claim. These elements include the misrepresentation or omission of material facts, and that the broker acted with intent or reckless disregard for the client’s needs.

The Sixth Circuit, however, held that SOX protects “all good faith and reasonable reporting of fraud,” with a focus on “employees’ reasonable belief rather than requiring them to ultimately substantiate their allegations.” Therefore, “an interpretation demanding a rigidly segmented factual showing justifying the employee’s suspicion undermines this purpose and conflicts with the statutory design.” The Sixth Circuit affirmed the jury verdict because there was sufficient evidence to sustain the jury’s finding that Mr. Rhinehimer reasonably believed that certain trades constituted unsuitability fraud. A contrary result would have resulted in employees—due to lack of tangible evidence—refraining from reporting fraud until after investors have already been harmed.

Generally, no. The great weight of authority holds that there is no independent materiality element to establish protected whistleblowing under Section 806 of SOX.

For example, in Donaldson v. Severn Sav. Bank, F.S.B.,[22] Vanessa L. Donaldson brought a SOX whistleblower action against her former employer, Severn Savings Bank (“Severn”), claiming she was unlawfully terminated after she reported to her supervisor her suspicions about an inaccurate bank report. Specifically, Ms. Donaldson alleged that she informed her supervisor about a scheme in which the commercial/retail manager for Ms. Donaldson’s branch falsified the retail production report for the third quarter of 2013, in order to collect unearned bonus pay.

Severn argued that Ms. Donaldson failed to allege she engaged in protected activity because she failed “to allege any facts whatsoever that would indicate any material misrepresentations (or omissions) were reported to Severn’s shareholders,” and so she lacked an objectively reasonable belief that she was disclosing shareholder fraud. The court rejected Severn’s narrow construction of SOX:

[T]he federal criminal fraud statutes . . . prohibit the scheme to defraud, not a completed fraud. . . .Materiality of falsehood . . . was a common-law element of actionable fraud at the time these fraud statutes were enacted and is an incorporated element of the mail fraud, wire fraud, and bank fraud statutes. . . . But § 1514A carries no independent materiality element. Consequently, Donaldson’s objective belief need not be about a material matter, as Severn has argued. Rather, her objective belief must be based on facts permitting an inference that [the manager’s] allegedly false representation was material to Severn’s course of conduct.[23]

The court found that Ms. Donaldson met this standard because the manager’s alleged inflation of the retail production figures was intended to, and likely would, affect the size of a bonus awarded him by Severn. Therefore, the court concluded, “it may be inferred from Donaldson’s complaint that she had an objectively reasonable belief that [the manager was] engaged in a scheme to defraud Severn.”[24]

Some of the options for a SOX whistleblower to prove that their disclosure was objectively reasonable include showing that the SEC had previously taken enforcement action to penalize conduct similar to that which the whistleblower opposed, and offering expert witness or coworker testimony indicating that other employees shared or agreed with the whistleblower’s concern.

A 2016 unpublished Fourth Circuit decision in Deltek, Inc. v. Dep't of Labor underscores the importance of coworker testimony in proving the objective reasonableness of a disclosure. [25] In this case, soon after starting a new job in the IT department of Deltek Inc., Ms. Gunther noticed a lack of clear procedure and documentation for Deltek’s billing disputes with Verizon Business. Ms. Gunther suspected that Deltek employees were subjecting Verizon to unfounded billing disputes in order to conceal a shortfall in Deltek’s telecommunications budget.

Ms. Gunther’s coworker, who was responsible for managing the billing relationship between Deltek and Verizon, agreed with her concerns, after which Ms. Gunther then reported to her immediate supervisor. Soon thereafter, Ms. Gunther began to experience hostility at work. She then escalated her concerns of ongoing fraud in a letter to Deltek’s general counsel, which she copied to the SEC. Deltek’s general counsel met with Ms. Gunther and asked her to gather information about her concerns. The general counsel then investigated Ms. Gunther’s report and found that no improper activity had occurred. Despite this, Ms. Gunther witnessed her coworkers shredding documents.

Eventually, Ms. Gunther was fired for being “confrontational and disruptive.” Deltek argued that Ms. Gunther’s belief that Deltek was violating securities laws was not objectively reasonable because she lacked the education and experience necessary to recognize securities fraud; she, in fact, did not have a college degree. The Fourth Circuit rejected this argument, stating that a determination of the reasonableness of Ms. Gunther’s belief warranted consideration of the “factual circumstances,” including information that Ms. Gunther learned from coworkers. The court agreed with the administrative law judge’s (ALJ’s) determination that “in forming her belief Gunther reasonably relied on her close dealings with [her coworker], who did have extensive experience in Verizon invoicing . . . [and] who was himself a ‘credible, convincing witness at the hearing.’” Therefore, the Fourth Circuit held Ms. Gunther’s belief that Deltek was violating securities laws as reasonable.

A consensus is emerging that the duty speech doctrine does not apply to SOX whistleblower claims.[26] The duty speech defense asserts that disclosures made while performing routine job duties are outside the ambit of protected conduct. The defense became increasingly popular in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 2006 decision in Garcetti v. Ceballos, which held that government employees cannot bring First Amendment whistleblower retaliation claims based on work-related speech if the speech is part of their job duties.[27]

Most Department of Labor (DOL) ALJs addressing this issue have declined to apply Garcetti to SOX claims. For example, Judge Lee Romero Jr. concluded that “one’s job duties may broadly encompass reporting of illegal conduct, for which retaliation results. Therefore, restricting protected activity to place one’s job duties beyond the reach of the Act would be contrary to congressional intent.”[28]

Recently, a New York district court held in Yang v. Navigators Grp., Inc. that the duty speech defense is inapplicable to SOX claims.[29] Jennifer Yang worked as the chief risk officer for Navigators Group (“Navigators”), an insurance company. Ms. Yang alleged that Navigators terminated her employment for disclosing to her supervisor deficient risk management and control practices. Navigators moved to dismiss Ms. Yang’s SOX claim in part on the basis that Yang’s disclosures about risk issues were “part and parcel of her job.”[30] The court rejected this duty speech argument, relying on a 2012 district court decision holding that “whether plaintiff’s activity was required by job description is irrelevant.”[31]

No: a whistleblower’s motives for engaging in protected conduct are irrelevant, per longstanding ARB precedent.[32] The whistleblower need only have a reasonable belief that the conduct violates federal securities laws or the other categories of protected conduct in Section 806 of SOX.

In certain circumstances, such disclosures could be protected under SOX, such as massive Medicare fraud that could result in a publicly traded company’s debarment from the Medicare program. But generally such disclosures are actionable under two whistleblower protection statutes: 1) the anti-retaliation provision of the False Claims Act; and 2) the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) whistleblower provisions. Click here to find out more about those whistleblower protection laws.

Certain disclosures about consumer financial fraud can be actionable under SOX. In addition, the whistleblower protection provision of the Consumer Financial Protection Act (CFPA) protects disclosures to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) or any local, state, or federal government authority or law enforcement agency concerning any act or omission that the employee reasonably believes to be a violation of any CFPB regulation or any other consumer financial protection law that the Bureau enforces. This includes several federal laws regulating unfair, deceptive, or abusive practices related to the provision of consumer financial products or services.

In recent years, a general consensus has emerged at the DOL and in federal courts about the broad scope of protected conduct under SOX. But some judges are determined to construe SOX narrowly and to impose burdens on SOX whistleblowers that are inconsistent with the plain meaning of the statute. Therefore, prior to invoking the option to remove a SOX complaint to federal court, it is important to research recent opinions in the relevant circuit concerning the scope of protected conduct.

The second element of a SOX claim is knowledge of protected conduct. A whistleblower may establish employer knowledge by demonstrating that a supervisor or senior executive knew of the activity (actual knowledge) or that a person with knowledge of the disclosure influenced the official who decided to take the retaliatory action (constructive knowledge).

Generally, no. In a SOX retaliation suit against an employer, a whistleblower need only make a protected disclosure to someone who has either supervisory authority over them or authority to investigate and address misconduct. The supervisor’s knowledge is imputed to the final decision-maker.[33]

SOX whistleblowers can demonstrate knowledge of protected conduct using the cat’s paw theory, i.e., by showing that the decision-maker followed the biased recommendation of a subordinate without independently investigating the reason or justification for the proposed adverse personnel action.

In Jayaraj v. Pro-Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,[34] the employer was a start-up biotechnology company whose primary executives were a chief executive officer (“CEO”) and a chief operating officer (“COO”). The CEO testified that when he decided to terminate the complainant’s employment, he was unaware that she had engaged in protected activities. However, based on evidence that the CEO and COO worked closely together since the founding of the company, the ALJ found that the COO had likely told the CEO about the complainant’s protected activity.

The SOX whistleblower-protection provision prohibits a broad range of retaliatory acts, including:

- termination;

- demotion;

- suspension;

- harassment; and

- any other form of discrimination that might dissuade a reasonable employee from whistleblowing.

The final catch-all category includes non-tangible employment actions, such as “outing” a whistleblower in a manner that forces the whistleblower to suffer alienation and isolation from work colleagues. SOX also proscribes a threat to retaliate.

Termination goes beyond “You’re fired!” Constructive discharge also constitutes an adverse employment action. This occurs where an employer has created “working conditions so intolerable that a reasonable person in the employee’s position would feel forced to resign,” or where the employer “acts in a manner so as to have communicated to a reasonable employee that [s/he] will be terminated, and the . . . employee resigns.” Under the latter standard, an employee facing “imminent discharge” may establish constructive discharge.[35]

Yes, disclosing a whistleblower’s identity may constitute an adverse employment action. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit reached this conclusion in a SOX case brought by Anthony Menendez, a former director in Halliburton Inc.’s finance and accounting department.[36]

About four months after Mr. Menendez joined Halliburton, he noticed that the company’s accounting practices that involved revenue recognition did not appear to conform to generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”). Mr. Menendez circulated a memo in his department about the issue. In response, his supervisor, who also received the memo, said that Mr. Menendez was not a “team player” and should work more closely with his colleagues to resolve accounting issues. Halliburton nonetheless studied the issue and, a couple of months later, determined that the accounting practices were proper.

After his supervisor refused a second meeting with him about the issue, Mr. Menendez filed a confidential disclosure with the SEC about Halliburton’s accounting practices. Mr. Menendez later raised the same issues in a memo to Halliburton’s board of directors. The memo was forwarded to Halliburton’s general counsel.

When Halliburton received a notice of investigation from the SEC requiring Halliburton to retain documents, Halliburton’s general counsel inferred from Mr. Menendez’s internal disclosures that he was the source of the SEC inquiry. The general counsel then sent an email to Mr. Menendez’s colleagues instructing them to retain certain documents because “the SEC has opened an inquiry into the allegations of Mr. Menendez,” effectively “outing” Mr. Menendez as a whistleblower.

Thereafter, Mr. Menendez’s colleagues began to treat him differently, refusing to work or associate with him. He resigned within a year. Applying the Burlington Northern material-adversity standard,[37] the Fifth Circuit concluded that “outing” Mr. Menendez was an actionable adverse action:

It is inevitable that such a disclosure would result in ostracism, and, unsurprisingly, that is exactly what happened to Menendez following the disclosure. Furthermore, when it is the boss that identifies one of his employees as the whistleblower who has brought an official investigation upon the department, as happened here, the boss could be read as sending a warning, granting his implied imprimatur on differential treatment of the employee, or otherwise expressing a sort of discontent from on high. . . . In an environment where insufficient collaboration constitutes deficient performance, the employer’s disclosure of the whistleblower’s identity and thus targeted creation of an environment in which the whistleblower is ostracized is not merely a matter of social concern, but is, in effect, a potential deprivation of opportunities for future advancement.[38]

When Halliburton outed Mr. Menendez to his colleagues as the whistleblower responsible for the SEC investigation, the company inevitably “creat[ed] an environment of ostracism,” which “well might dissuade a reasonable employee from whistleblowing.” This ruling underscores the broad scope of actionable retaliation under SOX.

The ARB and some district judges have held that SOX prohibits post-employment retaliation. For example, in Kshetrapal v. Dish Network, LLC,[39] Mr. Kshetrapal, an associate director for Dish Network (“Dish”), disclosed that a marketing agency with which Dish had contracted was submitting fraudulent bills. When Mr. Kshetrapal disclosed the fraud, his supervisors initially ignored him. Mr. Kshetrapal continued to press the issue, and Dish conducted an investigation, which resulted in Dish firing Mr. Kshetrapal’s supervisor and terminating its contract with the marketing agency. One month after taking these corrective actions, Dish forced Mr. Kshetrapal to resign.

The marketing agency sued Dish for breach of contract, and Mr. Kshetrapal was deposed in that litigation. During his deposition, Mr. Kshetrapal testified about the marketing agency’s fraud and his belief that his supervisor received bribes from the marketing agency. Shortly after the deposition, Mr. Kshetrapal began working for a music streaming service on which Dish ran ads. Upon learning that Mr. Kshetrapal worked for the music streaming service, Dish pulled its ads. Soon thereafter, a prospective employer of Mr. Kshetrapal rescinded a job offer because Dish ordered it not to hire Mr. Kshetrapal.

Mr. Kshetrapal sued Dish for retaliation, and in denying Dish’s motion to dismiss, Judge Crotty held that Mr. Kshetrapal’s deposition testimony about the alleged fraud was protected under SOX even though the deposition took place when he no longer worked for Dish. According to Judge Crotty, “a contrary holding would discourage employees from exposing fraudulent activities of their former employers for fear of retaliation in the form of blacklisting or interference with subsequent employment. Such a result would contravene the purpose of SOX.”[40] Some courts, however, have held that SOX does not proscribe post-termination retaliation.[41]

Yes. Discrete conduct occurring outside the statute of limitations may be circumstantial evidence of retaliation. An example is when a supervisor ultimately follows through on a threat to fire a whistleblower if the whistleblower raises additional compliance concerns. Even if the threat itself was made outside of the statute of limitations period, it is still relevant to prove retaliation.

“A contributing factor is any factor, which alone or in combination with other factors, tends to affect in any way the outcome of the decision.” Id. (quoting Klopfenstein v. PCC Flow Techs. Holdings, Inc., ARB No. 04-149, 2006 WL 3246904, at *13 (DOL May 31, 2006)).

In proving that protected activity was a contributing factor in the adverse action, a complainant need not necessarily prove that the respondent's articulated reason was a pretext. See Henderson v. Wheeling & Lake Erie Railway, ARB No. 11-013, ALJ No. 2010-FRS-12 (ARB Oct. 26, 2012) (citing Klopfenstein v. PCC Flow Techs. Holdings, Inc., ARB No. 04-149, ALJ No. 2004-SOX-011, slip op. at 18 (ARB May 31, 2006)). A complainant can prevail by showing that the respondent's reason, while true, is only one of the reasons for its adverse conduct and that another reason was the complainant's protected activity. Klopfenstein, ARB No. 04-149 at 19.

A whistleblower must demonstrate that their protected activity was a contributing factor in the decision to take an adverse action, i.e., that it was “more likely than not” played “any role whatsoever” in the allegedly retaliatory action.[42] And “any role whatsoever” is no exaggeration—the protected activity need not amount to a “significant, motivating, substantial or predominant” factor in the adverse action.[43]

A whistleblower may meet this burden by proffering circumstantial evidence, such as:

- Direct evidence of retaliatory motive, e., “statements or acts that point toward a discriminatory motive for the adverse employment action.”[44]

- Shifting or contradictory explanations for the adverse employment action.[45]

- Evidence of after-the-fact explanations for the adverse employment action. “[T]he credibility of an employer’s after-the-fact reasons for firing an employee is diminished if these reasons were not given at the time of the initial discharge decision.”[46]

- Animus or anger towards the employee for engaging in a protected activity.

- Significant, unexplained or systematic deviations from established policies or practices, such as failing to apply a progressive discipline policy to the whistleblower.[47]

- Singling out the whistleblower for extraordinary or unusually harsh disciplinary action.[48]

- Disparate treatment or proof that employees who are situated similarly to the plaintiff, but who did not engage in protected conduct, received better treatment.

- Close temporal proximity between the employee’s protected conduct and the decision to take an actionable adverse employment action.

- Evidence that the employer conducted a biased or inadequate investigation of the whistleblower’s disclosures, including evidence that the person accused of misconduct controlled or heavily influenced the investigation.

- The cost of taking corrective action necessary to address the whistleblower’s disclosures and the decision-maker’s incentive to suppress or conceal the whistleblower’s concerns.

- Corporate culture and evidence of a pattern or practice of retaliating against whistleblowers.

If the whistleblower proves “contributing factor” causation by a preponderance of the evidence, then the burden shifts to the employer to prove clearly and convincingly that it would have taken the same adverse action in the absence of the employee’s engagement in protected activity.

- In a mixed-motive case (where there is evidence of both a lawful and unlawful motive for the adverse action), does the evidence of a legitimate justification for the adverse action negate the whistleblower’s evidence that whistleblowing partially influenced the decision to take the adverse action?

A SOX whistleblower will typically prevail in a mixed-motive case because the SOX whistleblower’s burden is merely to show that protected activity played “any role whatsoever”—i.e., that it was a “contributing factor”—in the adverse employment action. If the decision-maker placed any weight whatsoever on the protected activity, then the whistleblower will establish causation.

The ARB has instructed ALJs to apply the following analysis in mixed-motive cases:

If the ALJ believes that the protected activity and the employer’s non-retaliatory reasons both played a role, the analysis is over and the employee prevails on the contributing-factor question. Thus, consideration of the employer’s non-retaliatory reasons at step one will effectively be premised on the employer pressing the factual theory that nonretaliatory reasons were the only reasons for its adverse action. Since the employee need only show that the retaliation played some role, the employee necessarily prevails at step one if there was more than one reason and one of those reasons was the protected activity.[49]

A SOX whistleblower is not required to disprove the employer’s allegedly legitimate, non-retaliatory reason for taking an adverse employment action.[50] But proof of pretext can prove causation. As the ARB observed in Palmer, “Indeed, at times, the factfinder’s belief that an employer’s claimed reasons are false can be precisely what makes the factfinder believe that protected activity was the real reason.”[51]

A SOX whistleblower need not demonstrate the existence of a retaliatory motive on the part of the employer to establish that protected activity was a contributing factor to the personnel action.[52] But evidence of a retaliatory motive, e.g., statement of retaliatory animus or resentment of the complainant’s whistleblowing, is relevant circumstantial evidence to prove retaliation.

Under certain circumstances, yes. Where an employer jumps on an employee’s first instance of misconduct or poor performance and subjects the employee to heightened scrutiny, the employer’s reliance on that alleged change in performance can be deemed a pretext for retaliation.

For example, in Colgan v. Fisher Scientific Co., an age-discrimination case, the Third Circuit held that Jack Colgan established pretext where Fisher Scientific terminated his employment shortly after Mr. Colgan declined an offer of early retirement, based on a single performance evaluation that was inconsistent with his thirty-year tenure at the company. Throughout his entire career as a machine operator with Fisher Scientific, Mr. Colgan regularly and consistently received positive performance evaluations. When he declined the company’s request that he retire, he was assigned substantial additional responsibilities and then the company gave him a surprise, premature evaluation, the worst he had received during his tenure at the company. The Third Circuit held that, in the context of Mr. Colgan’s long and well-rated service at Fisher Scientific, the single negative review was “compelling circumstantial evidence” that the company’s reliance on Mr. Colgan’s supposed performance issues was pretextual.[55]

An employer must prove clearly and convincingly that it would have taken the same adverse employment action even if the employee had not engaged in protected activity.[56] The operative phrase here is “would have.” An employer fails to meet its burden if it establishes merely that it could have taken the same adverse action. “Clear and convincing” evidence can be quantified as establishing the probability of a fact at issue “in the order of above 70%.”[57]

DOL ALJs assess the same-action affirmative defense using three discrete components.[58]

- First, the employer’s evidence must meet the plain meaning of “clear” and “convincing.” The employer must present a “highly probable,” unambiguous explanation for the adverse employment action. As the Supreme Court has held, evidence is clear and convincing only if it “immediately tilts the evidentiary scales in one direction.”[1]

- Second, the employer’s evidence must subjectively indicate that the employer “would have” taken the same adverse action absent the employee’s protected activity.

- And finally, material facts that the employer relied on to take the adverse personnel action must not change in the hypothetical absence of the protected activity. Here, the court evaluates how relevant facts would have differed without the protected activity.

That said, the employer bears this onerous burden only if an employee establishes that their protected activity contributed to the employer’s decision to take the adverse action against them.

For instance, an employer may rely on evidence that:

- the whistleblower recently performed poorly or otherwise gave the employer reason to take action;

- the employer’s reason for taking the adverse action materialized before the company allegedly engaged in misconduct or the employee blew the whistle; or

- the whistleblower’s personnel file supports the employer’s explanation and details the employer’s intent to take the adverse action.

A prevailing SOX whistleblower can recover “all relief necessary to make the employee whole,” which includes:

- back pay (lost wages and benefits);

- reinstatement with the same seniority that the employee would have had, were it not for the retaliation;

- special damages (damages for impairment of reputation, personal humiliation, mental anguish and suffering, and other noneconomic harm that results from retaliation); and

- attorney’s fees, and costs.[59]

Back pay includes promotions and salary increases that the whistleblower would have obtained but for the retaliation. Note that back pay is offset by interim earnings.

Uncapped special damages can be substantial where the retaliation has derailed the whistleblower’s career. “When reputational injury caused by an employer’s unlawful discrimination diminishes a plaintiff’s future earnings capacity, [they] cannot be made whole without compensation for the lost future earnings [they] would have received absent the employer’s unlawful activity.”[60] Therefore, it is important to proffer specific evidence of the impact of the retaliation on the whistleblower’s career prospects and the value of lost future earnings.

Yes. Although reinstatement is the preferred and presumptive remedy to make an employee whole, some SOX whistleblowers have recovered front pay in lieu of reinstatement. In Hagman v. Washington Mutual Bank, Inc., an ALJ awarded $640,000 in front pay to a banker whose supervisor became verbally and physically threatening when the banker disclosed concerns about the short funding of construction loans.[61]

In Deltek, the Fourth Circuit affirmed an award of approximately three and a half years of back pay (lost wages and benefits from the date of the termination of Ms. Gunther’s employment through the date of the hearing), plus four years of front pay and tuition benefits. The ALJ found that Ms. Gunther worked in administrative positions prior to working at Deltek and had been unable to obtain a finance position before and after her tenure at Deltek because she lacked a college degree. And since the ALJ found that Ms. Gunther was unlikely to find a comparable financial analyst position without a degree, the ALJ concluded that Ms. Gunther would need four years of front pay to account for the time Gunter would need to obtain a college degree, especially in the absence of the tuition-reimbursement benefits that Ms. Gunther was receiving while employed at Deltek.

On appeal, Deltek vigorously contested the front-pay award, contending that four years of front pay is unduly speculative. Noting that “some speculation about future earnings [was] necessary,” the court agreed with the ALJ’s finding that it would take Gunther four years to find comparable work. The court concluded that the ALJ and ARB “made the reasonable choice to assume that Gunther would have continued to earn the same salary and benefits at Deltek had she not been unlawfully terminated.”

No. But if a SOX whistleblower exercises the option to remove the claim to federal court, the whistleblower can potentially add other claims under which a prevailing party can recover punitive damages. For example, Mr. Sanford Wadler, a former in-house counsel at Bio-Rad, recovered $5 million in punitive damages in a retaliation action brought under SOX and under the California common law tort of wrongful discharge in violation of public policy. Mr. Wadler alleged that Bio-Rad terminated his employment because he raised concerns about potential violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The large award of punitive damages appears to have been motivated by the company’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) backdating a negative performance review of Mr. Wadler that the CEO drafted after firing Wadler. That review was an aberration from the positive reviews that Mr. Wadler received during his 25-year tenure at Bio-Rad. The company’s apparent attempt to create a post-hoc justification for the termination of Mr. Wadler’s employment may have backfired by enabling Mr. Wadler to prove malice and thereby recover punitive damages.

The U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration (“OSHA”) administers the anti-retaliation provision of SOX. A SOX whistleblower claim must be filed initially with OSHA. OSHA will then investigate the complaint and may order preliminary reinstatement of the whistleblowers if it finds “reasonable cause” to believe that retaliation occurred.

OSHA finds “reasonable cause” when it determines that a reasonable judge could rule for the whistleblower. And a reasonable judge could rule so only where there is evidence supporting each element of a SOX retaliation claim. Generally, though, less evidence is required to establish “reasonable cause” at this stage than to prevail at trial. “OSHA’s responsibility to determine whether there is reasonable cause to believe a violation occurred is greater than the complainant’s initial burden to demonstrate a prima facie allegation that is enough to trigger the investigation.”[62] But OSHA need not “resolve all possible conflicts in the evidence or make conclusive credibility determinations to find reasonable cause to believe that a violation occurred.” In practice, however, OSHA rules for SOX complainants only in the strongest cases, which is due in part to the burden that OSHA must bear to order preliminary reinstatement of a whistleblower.

A SOX whistleblower must file a complaint within 180 days after they either experience or become aware of the unlawful retaliation.[63] The clock starts ticking once “the discriminatory decision has been both made and communicated to the complainant.”[64] A complaint is considered filed once the Department of Labor receives it. A complaint sent by mail, however, is considered filed on the date of its postmark.

Though a discrete retaliatory act “occurs” on the day it happens and the complaint must be filed within 180 days, retaliatory acts outside the statute of limitations period are actionable where there is an ongoing hostile work environment and at least one of the acts occurred within the 180-day statute of limitations.

A SOX complaint need not plead every element of the claim in detail, but it must provide “fair notice” of the claim, which entails a showing of: 1) some facts about the protected activity; 2) some facts about the adverse action; 3) an assertion of causation, and 4) a description of the relief or damages sought by the whistleblower.[65]

SOX whistleblower complaints require less detail than claims filed in federal court. In other words, a SOX whistleblower need not meet the plausibility pleading standard that applies to actions filed in federal court.[66] But if the whistleblower anticipates removing the SOX claim to federal court, it may be advisable to file a detailed complaint. In particular, the complaint should plead every adverse action and each distinct category of protected activity.

Whistleblowers must initially file their SOX retaliation claims with OSHA.

No. SOX retaliation claims are categorically exempt from mandatory arbitration agreements.

Yes, OSHA can issue a preliminary order of reinstatement, which is not stayed pending an appeal of OSHA’s findings.

SOX retaliation claims are litigated before the Department of Labor Office of Administrative Law Judges or in federal court. SOX provides a right to de novo review in federal court after a complaint has been pending before the DOL for more than 180 days without a final decision. “De novo” review essentially means that a SOX whistleblower has an unwavering right to start afresh in district court, and the presiding judge should not defer to OSHA’s findings or to the ALJ’s rulings.[67]

Once OSHA completes its investigation, the whistleblower or the respondent (the former employer) may request a hearing before an ALJ at the Department of Labor. The hearing before the ALJ is de novo, i.e., the ALJ does not defer to OSHA’s findings.

A SOX whistleblower can file a petition for review with the ARB within 10 days after the ALJ renders a decision. The petition must identify every part of the ALJ’s decision that the whistleblower seeks to challenge.[68] The ARB will then decide whether to review the case. An ALJ’s decision becomes final after 10 days if no petition for review has been filed, or after 30 business days if the ARB has not issued an order accepting a timely filed petition for review.[69] If the ARB accepts the case for review, the ALJ’s decision is inoperative, but a reinstatement order becomes effective while the appeal is pending.[70]

The ARB reviews conclusions of law de novo and reviews the ALJ’s findings of facts under a substantial evidence standard.[71] A finding is supported by “substantial evidence” if evidence in the record logically supports the finding, and the record as a whole does not countervail that evidence.[72]

Note that the failure to appeal an ALJ decision can have a preclusive effect on other claims. For example, in Tice v. Bristol-Myers Squibb, the Third Circuit affirmed summary judgment for the employer, holding that a DOL ALJ’s determination that the employer had a legitimate reason for terminating SOX plaintiff Carol Tice’s employment should be accorded preclusive effect in related employment actions.[73] Ms. Tice had initially filed a SOX retaliation claim with OSHA, alleging that her employment was terminated in violation of SOX because she opposed management’s direction to employees to falsify sales call reports. A SOX ALJ dismissed Ms. Tice’s claim, concluding that the employer demonstrated that it would have terminated Ms. Tice absent her disclosure because Ms. Tice herself falsified sales call reports. Ms. Tice did not appeal the ALJ’s order and subsequently brought a separate action against her former employer in federal court alleging age discrimination and gender discrimination. The summary judgment dismissal of Ms. Tice’s discrimination claims likely could have been avoided if Ms. Tice had appealed the DOL ALJ’s order.

Yes. The prevailing party before the ALJ can request ARB review within 10 days after the ALJ issues its decision if that party may later want to appeal a portion of that decision.

A SOX whistleblower may, within 60 days of the ARB’s issuing its final decision, file a petition for review to the U.S. Court of Appeals in the circuit in which the alleged SOX violation occurred, or in the circuit in which the complainant resided on the date of the alleged violation.

SOX does not specify a standard of review for appeals to the federal courts of appeals. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, a court of appeals will uphold an ALJ’s findings of fact if supported by “substantial evidence.” The court reviews questions of law de novo, deferring to the ARB’s interpretation of statutes administered by the Department of Labor.

Yes, though not initially. A SOX whistleblower case must first be filed with OSHA. One hundred and eighty days after filing, the whistleblower may remove the claim from DOL and file it in federal court.[74]

SOX’s “kick-out” provision, which authorizes this type of removal, may allow whistleblowers to recover more than they could on SOX claims alone. That’s because, although SOX does not authorize punitive damages, a SOX plaintiff in federal court may add claims for which punitive damages can be recovered, such as a common-law claim of wrongful discharge in violation of public policy.

Section 806 of SOX does not specify a time limit for filing a SOX complaint in district court after removal of the case from the Department of Labor by the complainant. Though a Kansas federal judge found that there is no time limitation for filing a removed SOX claim in federal court, the Fourth Circuit held that a SOX claim must be filed in federal court within four years after the complaint is removed from DOL.[75]

Yes. Section 806 of SOX, as amended by the Dodd-Frank Act, explicitly states that parties to SOX whistleblower actions are entitled to a trial by jury.[76] And some SOX whistleblowers have obtained substantial recoveries after invoking their right to a jury trial.

Juries may award substantial compensatory damages even if a whistleblower has not suffered great economic loss.

One such whistleblower is Julio Perez, who recovered nearly $5 million in a SOX whistleblower retaliation case that he tried before a jury.[77] Dr. Perez, a former senior manager of pharmaceutical chemistry for Progenics Pharmaceuticals Inc., developed a medication with his Progenics colleagues and representatives from another pharmaceutical company. During the drug’s clinical trials, Dr. Perez saw a confidential memo that contradicted the pharmaceutical companies’ public statements about the drug.

Dr. Perez reported to Progenics executives that he believed the company was committing fraud against its shareholders by making public representations about the drug that were inconsistent with the clinical-trial results. Later the same day, after Dr. Perez was locked out of Progenics’ computer system, the company’s CFO tracked him down to ask how he had obtained the confidential memo. Dr. Perez asked for time to discuss the issue with his lawyer, and the CFO assented. The next morning, however, the company’s CFO and general counsel met with Dr. Perez and fired him on the spot for misappropriating the confidential memo.

Dr. Perez then filed a SOX retaliation claim with OSHA. Progenics claimed that it terminated Dr. Perez’s employment because he refused to explain how he obtained the confidential memo. Dr. Perez argued that he received the document via interoffice mail, that the memo was widely distributed within the partner pharmaceutical company, and that his position generally granted him access to clinical-trial results.

OSHA did not substantiate his complaint and he removed his claim to federal court. After years of contentious litigation, the case went to trial, and the jury awarded Dr. Perez $1.6 million in compensatory damages. The court’s award of back pay and front pay resulted in a total recovery of close to $5 million. Corporate Counsel published a story describing Dr. Perez’s seven-year ordeal, entitled How to Help a Whistleblower.

Another SOX whistleblower, Catherine Zulfer, also received a substantial award from a jury in March 2014.[78] Ms. Zulfer was an accounting executive for Playboy Inc., her employer of more than three decades. Ms. Zulfer suspected that something was amiss when the company’s new CFO repeatedly instructed her to set aside $1 million for executive bonuses that had not been approved by the board of directors. Seeing no legitimate basis for discretionary bonuses on a year that Playboy suffered substantial losses, Ms. Zulfer suspected that the CFO and CEO were attempting to embezzle the money. So she refused to carry out the CFO’s orders, believing that it would be dishonest to shareholders and violate generally accepted accounting principles. Ms. Zulfer also reported her concerns to the company’s general counsel and outside SEC counsel.

Immediately thereafter, the Playboy CFO retaliated by ostracizing Ms. Zulfer, excluding her from meetings, forcing her to take on additional duties, and eventually terminating her employment. After a short trial, a federal jury in California awarded Ms. Zulfer $6 million in damages and ruled that she was also entitled to punitive damages. Ms. Zulfer and Playboy reached a settlement before a determination of punitive damages was made.

Finally, whistleblowers Shawn and Lena Van Asdale won substantial damages at trial and the Ninth Circuit affirmed the award.[79] The Van Asdales, a married couple, both served as in-house counsel at International Game Technology (“IGT”), a position they continued to hold after the company merged with a rival game company, Anchor Gaming. Following the merger, the Van Asdales discovered that Anchor had withheld material information about its value, causing IGT to commit shareholder fraud by paying more than market value to acquire Anchor. The Van Asdales reported their concerns to their boss, who had served as Anchor’s general counsel prior to the merger. Both Van Asdales were fired shortly thereafter.

The Van Asdales filed a SOX claim, alleging that they had been terminated in retaliation for disclosing shareholder fraud related to IGT’s merger with Anchor. A federal jury in Nevada eventually awarded the Van Asdales $2.2 million in compensatory damages and $2.4 million in attorney’s fees. The Ninth Circuit affirmed the award.

SOX whistleblowers are generally able to take broad discovery to prove their claims. Requests for discovery are permitted unless the information sought has “no possible bearings on a party’s claims or defenses.”[80]

Formal rules of evidence do not apply in SOX whistleblower cases litigated before a DOL ALJ. Evidentiary rules substantially similar to the Federal Rules of Evidence, however, apply.[81] The Office of ALJ, within the Department of Labor, has adopted those rules to ensure that the most probative evidence is produced.[82] Evidence that is immaterial, irrelevant, or unduly repetitious may be excluded.[83]

No. Section 806 of SOX specifically provides that “[n]othing in this section shall be deemed to diminish the rights, privileges, or remedies of any employee under any Federal or State law, or under any collective bargaining agreement.”[84] A whistleblower who is fired for refusing to commit an illegal act could bring both a SOX claim and a common-law wrongful discharge claim. Bringing the latter claim could potentially result in an award of punitive damages. But note that in some states, where there is an adequate statutory remedy to vindicate the public policy objectives, the employee can pursue a retaliation action only through the statute.

[1] Colorado v. New Mexico, 467 U.S. 310 (1984).

[1] S. Rep. No. 107-146, at 4–5 (2002).

[2] Lawson v FMR LLC, 134 S.Ct. 1158, 1162 (2014).

[3] ACFE’s 2016 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse, available at https://www.acfe.com/rttn2016.aspx.

[4] Ethics Resource Center, Retaliation: When Whistleblowers Become Victims. A supplemental report of the 2011 National Business Ethics Survey, available at https://s3.amazonaws.com/berkley-center/120101NationalBusinessEthicsSurvey2011WorkplaceEthicsinTransition.pdf.

[5] See Lawson, 134 S. Ct. 1158.

[6] See Anthony v. Nw. Mut. Life Ins. Co., 130 F. Supp. 3d 644 (N.D.N.Y. 2015); see also Gibney v. Evolution Mktg. Research, LLC, 25 F. Supp. 3d 741 (E.D. Pa. 2014).

[7] Fleszar v. U.S. Dep't of Labor, 598 F.3d 912, 915 (7th Cir. 2010)

[8] Bechtel v. Admin. Review Bd., 710 F.3d 443, 447 (2d Cir. 2013)

[9] Wiest v. Lynch, 710 F.3d 121, 132 (3d Cir. 2013)

[10] Leshinsky v. Telvent GIT, S.A., 942 F.Supp.2d 432, 444 (S.D.N.Y.2013) (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

[11] Legislative History of Title VIII of HR 2673: The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, Cong. Rec. S7418, S7420 (daily ed. July 26, 2002), available at 2002 WL 32054527.

[12] Sylvester v. Parexel Int’l LLC, ARB Case No. 07-123, at 19 (ARB May 25, 2011).

[13] Wiest, 710 F.3d at 132.

[14] Sylvester v. Parexel, ARB Case No. 07-123, 2011 WL 2165854 at *13 (DOL May 25, 2011).

[15] Murray v. UBS Securities, LLC, 2017 WL 1498051 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 25, 2017).

[16] Id. (citations omitted).

[17] Nielsen v. AECOM Tech. Corp., 762 F.3d 214, 224 (2d Cir. 2014)

[18] Murray, 2017 WL 1498051, at *10.

[19] Id., at *10 (quoting Guyden v. Aetna, Inc., 544 F.3d 376, 384 (2d Cir. 2008), superseded on other grounds by statute).

[20] Id., at *9 (quoting Nielsen, 762 F.3d at 221 (alterations in original)).

[21] Rhinehimer v. U.S. Bancorp Invs., Inc., 787 F.3d 797 (6th Cir. 2015).

[22] No. JKB-15-901, 2015 WL 7294362, at *3 (D. Md. Nov. 18, 2015).

[23] Id. at *3 (citations omitted).

[24] Id.

[25] See Deltek, Inc. v. Dep’t of Labor, Admin. Review Bd., No. 14-2415, 2016 WL 2946570 (4th Cir. May 20, 2016).

[26] See, e.g., Robinson v. Morgan Stanley, ARB Case No. 07-070, 2010 WL 348303, at *8 (Jan. 10, 2010) (“[Section 1514A] does not indicate that an employee’s report or complaint about a potential violation must involve actions outside the complainant’s assigned duties.”).

[27] See Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410, 422 (2006).

[28] Deremer v. Gulfmark Offshore, Inc., ALJ Case No. 2006-SOX-2, 2007 WL 6888110, at *42 (June 29, 2007).

[29] See Yang v. Navigators Grp., Inc., 18 F. Supp. 3d 519, 530 (S.D.N.Y. May 8, 2014).

[30] Id.

[31] See id. at 531 (citing Barker v. UBS AG, 888 F. Supp. 2d 291, 297 (D. Conn. 2012)).

[32] See Henderson v. Wheeling & Lake Erie Ry., ARB No. 11-013, ALJ No. 2010-FRS-012, slip op. at 14 (ARB Oct. 26, 2012); Malmanger v. Air Evac EMS, Inc., ARB No. 08-071, slip op. at 10-11, ALJ No. 2007-AIR-8 (ARB July 2, 2009).

[33] Leznik v. Nektar Therapeutics, Inc., ALJ Case No. 2006-SOX-00093 (Dep’t of Labor Nov. 16, 2007).

[34] 2003-SOX-32 (ALJ Feb. 11, 2005).

[35] Dietz v. Cypress Semiconductor Corp., ARB Case No. 15-017, 2016 WL 1389927, at *7(ARB Mar. 30, 2016).

[36] See Halliburton, Inc. v. Admin. Review Bd., 771 F.3d 254 (5th Cir. 2014).

[37] Burlington N. & Santa Fe Ry. Co. v. White, 548 U.S. 53 (2006).

[38] Halliburton, Inc. v. Admin. Review Bd., 771 F.3d at 262.

[39] 90 F. Supp. 3d 108, 112–14 (S.D.N.Y. 2015).

[40] Id. at 114.

[41] See, e.g., Hughart v. Raymond James & Assocs., Inc., 2004 DOLSOX LEXIS 92, at* 129 (ALJ Dec. 17, 2004)

[42] Palmer v. Canadian National Railway, ARB No. 16-035 at 53 (citations omitted).

[43] Allen v. Stewart Enters., Inc., ARB Case No. 06-081, slip op. at 17 (U.S. Dep’t of Labor July 27, 2006).

[44] William Dorsey, An Overview of Whistleblower Protection Claims at the United States Department of Labor, 26 J. Nat'l Ass'n Admin. L. Judiciary 43, 66 (Spring 2006) (citing Griffith v. City of Des Moines, 387 F.3d 733 (8th Cir. 2004)).

[45] Clemmons v. Ameristar Airways, Inc., ARB No. 08-067, at 9, ALJ No. 2004-AIR-11 (ARB May 26, 2010) (footnotes omitted).

[46] Id. at 9-10 (footnotes omitted).

[47] Bobreski v. J. Givoo Consultants, Inc., ARB No. 13-001, ALJ No. 2008-ERA-3 (ARB Aug. 29, 2014).

[48] See Overall v. TVA, ARB Nos. 98-111 and 128, slip op. at 16-17 (Apr. 30, 2001), aff'd TVA v. DOL, 59 F. App’x 732 (6th Cir. 2003).

[49] Palmer v. Canadian National Railway, ARB No. 16-035 at 56-57 (citations omitted).

[50] Zinn v. American Commercial Lines, Inc., ARB No. 10-029, ALJ No. 2009-SOX-025, 2012 WL 1143309, *7 (ARB Mar. 28, 2012); Warren v. Custom Organics, ARB No. 10-092, ALJ No. 2009-STA-030, 2012 WL 759335, *5 (ARB Feb. 29, 2012); Klopfenstein v. PCC Flow Tech., Inc., ARB No. 04-149, ALJ No. 04-SOX-11, 2006 WL 3246904, *13 (ARB May 31, 2006).

[51] Palmer, ARB No. 16-035 at 54 (citations omitted).

[52] Marano v. U.S. Dep’t of Justice, 2 F.3d 1137, 1141 (Fed. Cir. 1993).

[53] Vannoy v. Celanese Corp., ARB No. 09-118, ALJ No. 2008-SOX-64 (ARB Sept. 28, 2011).

[54] Van Asdale v. International Game Technology, 577 F.3d 989, 1003 (9th Cir. 2009).

[55] Colgan v. Fisher Scientific Co., 935 F.2d 1407 (3d Cir. 1991) (en banc), cert denied 502 U.S. 941, 112 S. Ct. 379 (1991).

[56] See Menendez v. Halliburton, Inc., ARB Case Nos. 09-002, 09-003, 2011 WL 4915750, at 6 (Sept. 13, 2011).

[57] Palmer v. Canadian National Railway, ARB No. 16-035 at 57.

[58] Speegle v. Stone & Webster Construction, Inc., ARB Case No. 13-074, 2014 WL 1758321 (ARB Apr. 25, 2014).

[59] 18 U.S.C. § 1514A(c).

[60] Mahony v. KeySpan Corp., No. 04 Civ. 554 (SJ), 2007 WL 805813, at *1 (E.D.N.Y. Mar. 12, 2007).

[61] ALJ Case No. 2005-SOX-00073, at 26–30 (ARB Dec. 19, 2006), appeal dismissed, ARB Case No. 07-039 (ARB May 23, 2007)

[62] Clarification of the Investigative Standard for OSHA Whistleblower Investigations (Apr. 20, 2015)

[63] 18 U.S.C. §1514A(b)(2)(D).

[64] 29 CFR § 1980.103(d).

[65] Johnson v. The Wellpoint Companies, Inc., ARB No. 11-035, ALJ No. 2010-SOX-38 (ARB Feb. 25, 2013).

[66] Sylvester v. Parexel Int’l. LLC, ARB No. 07-123, ALJ Nos. 2007-SOX-39 & 42 (ARB May 25, 2011).

[67] Stone v. Instrumentation Lab. Co., 591 F.3d 239 (4th Cir. 2009).

[68] 29 C.F.R. § 1980.110(a).

[69] 29 CFR § 1980.110(b).

[70] 29 CFR § 1980.110(b).

[71] Clark v. Hamilton Hauling, LLC, ARB No. 13-023, ALJ No. 2011-STA-7, at 4-5 (ARB May 29, 2014).

[72] Bobreski v. J. Givoo Consultants, Inc., ARB No. 13-001, ALJ No. 2008-ERA-3, at 13-14 (ARB Aug. 29, 2014).

[73] Tice, 325 F. App’x 114 (3d Cir. 2009).

[74] 18 U.S.C. § 1514A(b)(1)(B).

[75] Jones v. Southpeak Interactive Corp., 777 F.3d 658 (4th Cir. 2015).

[76] 18 U.S.C. 1514A(b)(2)(E).

[77] See Perez v. Progenics Pharm., Inc., 965 F. Supp. 2d 353, 359 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

[78] Zulfer v. Playboy Enters. Inc., JVR No. 1405010041, 2014 WL 1891246 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 5, 2014).

[79] Van Asdale v. Int’l Game Tech., 549 F. App’x 611, 614 (9th Cir. Sept. 27, 2013).

[80] Leznik v. Nektar Therapeutics, Inc., 2006-SOX-93 (ALJ Feb. 9, 2007).

[81] See 29 CFR § 18.101 et seq.

[82] 29 CFR § 1980.107(d).

[83] Leznik v. Nektar Therapeutics, Inc., 2006-SOX-93 (ALJ Feb. 9, 2007).

[84] 18 U.S.C. § 1514A(d).

Recommended Posts

-

For too long, taxpayers have been subsidizing whistleblower retaliation by paying legal costs incurred…

-

UPDATE: In Digital Realty Trust, Inc. v. Somers, the Supreme Court clarified the scope of…

-

DC whistleblower lawyer Jason Zuckerman spoke at a Bloomberg BNA CLE about recent developments in…

-

Whistleblower lawyer Jason Zuckerman will be speaking on a panel titled “Developments and Trends…