Pleading Qui Tam False Claims Act Case in Detail

False Claims Act qui tam actions must meet the heightened pleading requirement set forth in Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 9(b). In other words, a quit tam relator must “state with particularity the circumstances constituting fraud.” Fed. R. Civ. P. 9(b). The complaint must “identify ‘the who, what, when, where, and how of the misconduct charged,’ as well as ‘what is false or misleading about [the purportedly fraudulent] statement, and why it is false.’” Cafasso ex rel. United States v. General Dynamics C4 Systems, Inc., 637 F.3d 1047, 1055 (9th Cir. 2011)

Note though that in the Ninth Circuit, the relator need not “identify representative examples of false claims to support every allegation.” Ebeid ex rel. U.S. v. Lungwitz, 616 F.3d 993, 998 (9th Cir. 2010). Similarly, in the Eleventh Circuit, there is no requirement for a qui tam relator to provide exact billing data. Clausen v. Lab. Corp. of Am., Inc., 290 F.3d 1301, 1312 & n.21 (11th Cir. 2002). Rather, a complaint must contain “some indicia of reliability” that a false claim was actually submitted. Clausen, 290 F.3d at 1311. “For instance, a relator with first-hand knowledge of the defendant’s billing practices may possess a sufficient basis for alleging that the defendant submitted false claims.” United States ex rel Patel v. GE Healthcare, Inc., No. 8:14-cv-120-T-33TGW, 2017 WL 4310263, at *6 (M.D. Fla. Sept. 28, 2017).

“An FCA claimant is not required to show `the exact content of the false claims in question’ to survive a motion to dismiss, as `requiring this sort of detail at the pleading stage would be one small step shy of requiring production of actual documentation with the complaint, a level of proof not demanded to win at trial and significantly more than any federal pleading rule contemplates.'” United States v. Executive Health Resources, Inc., 196 F.Supp.3d 477, 492 (E.D.Pa. 2016) (citing Foglia, 754 F.3d at 156); Gohil, 96 F.Supp.3d at 519 (“[A relator] is not required to plead the details of any false claim submitted for payment[.]”)

But it is critical to connect the fraud scheme to the submission of false claims. In United States ex rel. Booker v. Pfizer, Inc., 847 F.3d 52, 58 (1st Cir. 2017), the First Circuit held that “aggregate [information] reflecting the amount of money expended by Medicaid” on off-label prescriptions was “insufficient on its own to support a[] [False Claims Act] claim” because it did not show “an actual false claim made to the [G]overnment.”

To satisfy Rule 9(b), the whistleblower “must provide ‘particular details of a scheme to submit false claims paired with reliable indicia that lead to a strong inference that claims were actually submitted’”; “[d]escribing a mere opportunity for fraud will not suffice.” See Foglia v. Renal Ventures Mgmt., 754 F.3d 153, 157-58 (3d Cir. 2014).

As summarized in United States of America ex rel. Donna Rauch v. Oaktree Medical Centre, P.C., No. 6:15-cv-01589 (D.SC March 5, 2020), the Fourth Circuit applies the following Rule 9(b) standard:

“To satisfy Rule 9(b), a plaintiff asserting a claim under the [FCA] `must, at a minimum, describe the time, place, and contents of the false representations, as well as the identity of the person making the misrepresentation and what he obtained thereby.'” Nathan, 707 F.3d at 455-56 (quoting United States ex rel. Wilson v. Kellogg Brown & Root, Inc., 525 F.3d 370, 379 (4th Cir. 2008)). The Fourth Circuit has held that “allegations of a fraudulent scheme, in the absence of an assertion that a specific false claim was presented to the government for payment” are insufficient to meet Rule 9(b)’s heightened pleading standard. Id. at 456. “Instead, the critical question is whether the defendant caused a false claim to be presented to the government, because liability under the [FCA] attaches only to a claim actually presented to the government for payment, not the underlying fraudulent scheme.” Id. (citing Harrison, 176 F.3d at 785). In the event a relator does not plead with particularity that specific false claims actually were presented to the government for payment, a relator’s complaint may still survive a Rule 9(b) challenge only if it “allege[s] a pattern of conduct that would `necessarily have led[ ] to submission of false claims’ to the government for payment.” Grant, 912 F.3d at 197 (quoting Nathan, 707 F.3d at 457) (alteration and emphasis in original).

Elements of a False Claims Act Qui Tam Case

A qui tam relator must plead:

- a false statement or fraudulent course of conduct;

- made with scienter (intent);

- that was material; and

- causing the government to pay out money or forfeit moneys due.

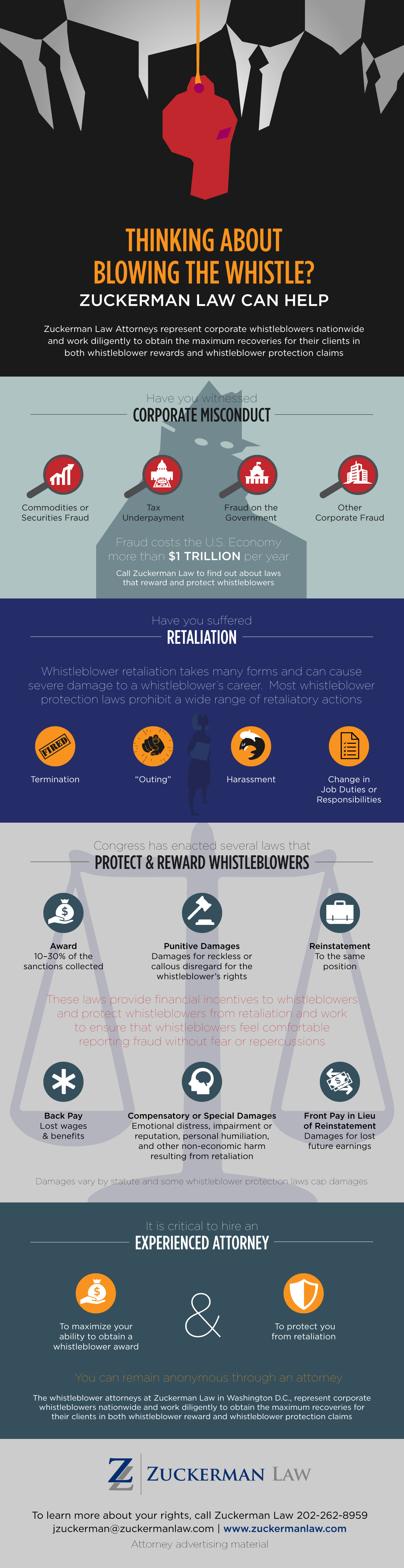

False Claims Act Whistleblower Lawyers

If you are seeking representation in a False Claims Act case, call leading whistleblower law firm Zuckerman Law today to schedule a free consultation. We can be reached at 202-262-8959.

False Claims Act Whistleblower Resources

- What is a qui tam whistleblower lawsuit?

- What types of false claims are prohibited by the False Claims Act?

- What is the first-to-file bar in False Claims Act qui tam cases?

- What is the requirement to file a False Claims Act qui tam action under seal?

- What is a reverse false claim?

- What is the statute of limitations for a False Claims Act qui tam action?

- What is the public disclosure bar in the False Claims Act?

- What is the original source exception to the public disclosure bar?

- What is materiality under the False Claims Act?

- What is “Scienter” Under the False Claims Act?

- Is a Violation of the Anti-Kickback Law Also a Violation of the False Claims Act?

- Does the False Claims Act Prohibit Bid-Rigging?

- Does the False Claims Act Prohibit Fraudulent Inducement of a Contract?

- Can a violation of Good Manufacturing Practices give rise to False Claims Act Liability?

- Is there a heightened pleading requirement for False Claims Act qui tam cases?

- Does the False Claims Act authorize treble damages?

- Must a False Claims Act qui tam relator have firsthand knowledge of all aspects of the fraud?

Qui Tam Relators Can Satisfy Rule 9(b) with Examples Rather than a Comprehensive List of False Claims

As Judge Trauger held in United States ex rel. Anderson v. Curo Health Servs. Holdings., No. 3:13-cv-00672 (M.D. Tenn. March 21, 2022):

The infeasibility of such a standard becomes clear if one attempts to apply it to any number of ordinary types of FCA case. Imagine, for example, that the United States or a relator was pursuing a company-wide FCA case against a large national pharmacy chain. See, e.g., U.S. ex rel. Kester v. Novartis Pharms. Corp. et al., 43 F. Supp. 3d 332, 342 (S.D.N.Y. 2014). Would Rule 9(b) require the complaint to include an example from every pharmacy location for every segment of the underlying time period, even if that meant thousands of examples and a complaint the length of an encyclopedia volume? The defendants have found no court that has endorsed such a reading. Aside from the fact that so stringent a standard would serve very little purpose, it would also be impossible to reconcile with the “general policy of `simplicity and flexibility’ in pleadings” that, the Sixth Circuit has held, Rule 9(b) does not negate. SNAPP, Inc., 532 F.3d at 504.

The reason that courts allow FCA plaintiffs to satisfy Rule 9(b) with examples, rather than a comprehensive list of individual claims, is that achieving that level of specificity and granularity for every false claim would, at least in a case like this one, “be extremely ungainly, if not impossible.” Bledsoe, 501 F.3d at 509 (citing U.S. ex rel. Franklin v. Parke-Davis, Div. of Warner-Lambert Co., 147 F.Supp.2d 39, 49 (D. Mass. 2001)). A policy of requiring separate examples for every conceivable variation on the ancillary details of the underlying claims would pose the same problem. There is, of course, a limit to how much a plaintiff can rely on one example to support an array of attenuated theories of liability. What qualifies as a sufficient set of examples for any given case, however, depends on the nature of the allegations at issue, not on a rote checklist of dates and service locations. For example, in United States ex rel. Hinkle v. Caris Healthcare, L.P., No. 3:14-CV-212-TAV-HBG, 2017 WL 3670652 (E.D. Tenn. May 30, 2017), the District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee concluded that the government’s description of “six `audit sample patients’ in detail” amounted to “sufficient illustrative examples of patients whom defendants allegedly knew did not qualify for hospice treatment” for the purposes of the twenty-six facilities at issue, because those examples, combined with the government’s pleading of the general scheme itself, “g[ave] defendants fair notice of the FCA claims brought against them under Rules 8 and 9(b).” Id. at *3, *9-10. The pattern in this case is almost identical: the governments provided multiple examples to demonstrate a statewide problem of improper hospice certification. In this case, like in that one, the examples are adequate.

The governments in this case have alleged a coherent, specific pattern whereby (1) corporate pressure placed a thumb on the scales in favor of improper admissions and (2) the personnel in individual agencies predictably responded by admitting and/or retaining patients who did not qualify for hospice by any reasonable clinical standard. Although some Avalon agencies may have been worse than others, the top-down, corporate policies that drove all of the alleged false claims were not limited to any specific Avalon location, and the plaintiffs have provided examples from multiple Avalon locations, at multiple times, which illustrate the ways in which the scheme resulted in fraud against the Medicare and Medicaid systems. In the absence of some specific, binding authority suggesting that such pleading was nevertheless insufficient, the court will not prematurely dismiss any aspect of the plaintiffs’ claims based on supposed noncompliance with pleading requirements.