Scope of Sarbanes-Oxley Corporate Whistleblower Protection

The whistleblower protection provision of SOX protects:

- employees, officers, and agents of publicly traded companies (companies issuing securities registered under section 12 of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 or required to file reports under section 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934);

- employees of any subsidiary or affiliate of a publicly-traded company whose financial information is included in the consolidated financial statements of such company;

- employees of contractors or subcontractors of public companies, including the attorneys and accountants who prepare public companies’ SEC filings;[i] and

- employees of nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (as defined in section 3(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (15 U.S.C. 78c).

Employees not protected by SOX may have a remedy under other whistleblower protection laws.

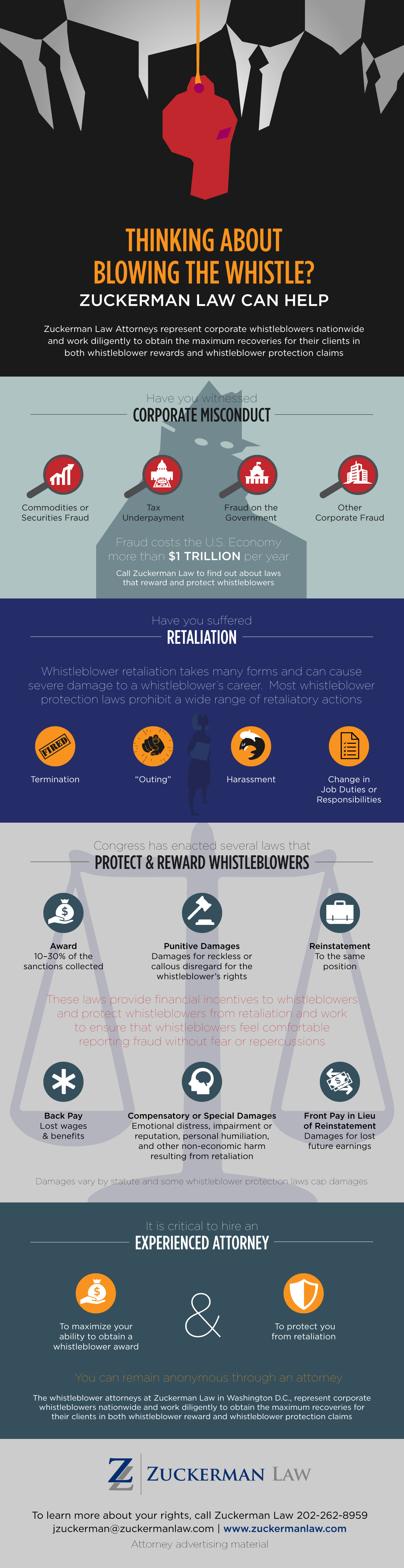

Leading Sarbanes-Oxley whistleblower firm Zuckerman Law represents whistleblowers nationwide. If you are seeking representation in a whistleblower retaliation or whistleblower protection case, click here, or call our whistleblower retaliation lawyers at 202-262-8959 to schedule a confidential consultation.

SOX Whistleblower Protection for Contractors of Public Companies

There are, however, some limitations on SOX coverage for employees of contractors of publicly traded companies:

- “Contractor” is limited to business relationships where “performance of a contract will take place over a significant period of time.”

- SOX “protects contractor employees only to the extent that their whistleblowing relates to ‘the contractor … fulfilling its role as a contractor for the public company, not the contractor in some other capacity.’” In other words, SOX protects a contractor employee who is in a position to detect and report securities violations — for example, the lawyers and accountants in the Enron scandal who were either directly or indirectly witness to the fraud.

- SOX does not cover contractor employees who experience retaliation that is unrelated to the provision of services to a public company. [ii] A contractor’s fraudulent practices do not become subject to § 1514A merely because that company incidentally has a contract with a public company.[iii]

[i] See Lawson, 134 S. Ct. 1158.

[ii] See Anthony v. Nw. Mut. Life Ins. Co., 130 F. Supp. 3d 644 (N.D.N.Y. 2015); see also Gibney v. Evolution Mktg. Research, LLC, 25 F. Supp. 3d 741 (E.D. Pa. 2014).

[iii] Fleszar v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor, 598 F.3d 912, 915 (7th Cir. 2010)

SOX Coverage for Employees of Affiliates of Public Companies

In a decision denying a motion to dismiss, DOL ALJ Nordby discussed the scope of coverage for employees of affiliates of public companies:

“[A]n “affiliate” is defined by Black’s Law Dictionary, in the context of securities, as ‘[o]ne who controls, is controlled by, or is under common control with an issuer of a security.” Rothstein v. Am. Int’l Grp., Inc., 837 F.3d 195, 206 (2d Cir. 2016) (quoting Affiliate, Black’s Law Dictionary (10th ed. 2014)). Similarly, the Securities and Exchange Commission(“SEC”) defines “affiliate” as a “person that directly, or indirectly through one or more intermediaries, controls, or is controlled by, or is under common control with, such issuer.” 17 C.F.R. §230.144(a)(1).” Kim v. SK Hynix Memory Solutions, 2019-SOX-12 (ALJ Nov. 4, 2019).

The question of control is highly fact-dependent, and will often turn on the resolution of disputed facts.

Supreme Court Holds that Sarbanes-Oxley Protects Employees of Contractors of Public Companies

In March 2014, the Supreme Court clarified that employees of contractors of public companies, including the attorneys and accountants who prepare the SEC filings of public companies, are covered under Section 806. See Lawson v. FMR LLC, 134 S. Ct. 1158 (2014). Subsequent interpretations of Lawson, however, suggest that the disclosures of a contractor’s employee are protected only if those disclosures pertain to fraud perpetrated by a publicly-traded company, as opposed to wrongdoing by a private contractor.

Jackie Lawson worked for Fidelity Brokerage Services, a private subsidiary of the private company FMR Corp., which manages the day-to-day operations of publicly traded Fidelity mutual funds.[2] As is common in the mutual-fund industry, the Fidelity investment company that files reports with the SEC (and is covered under Section 806) does not direct the personnel who operate the funds on a day-to-day basis. Lawson brought a SOX claim alleging retaliation for disclosing securities violations, including improper retention of advisory fees. The district court held that Lawson is a covered employee under Section 806, but the First Circuit reversed, holding that SOX protects only employees of publicly traded companies.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court reversed, holding that SOX protects employees of contractors, subcontractors, and agents of public companies. Lawson, 134 S. Ct. at 1176. The majority relied primarily on the plain meaning of SOX but also based its decision on an extensive examination of the legislative history and purpose of the statute. In particular, the Court focused on references in the legislative history to outside auditors and attorneys who suffered retaliation after blowing the whistle on accounting fraud at Enron. The Court concluded that protecting employees of contractors of public companies is essential to preventing another Enron.

In the wake of Lawson, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania interpreted a limiting principle for SOX coverage of employees of public companies’ contractors and subcontractors. See Gibney v. Evolution Mktg. Research, LLC, 25 F. Supp. 3d 741 (E.D. Pa. 2014). Leo Gibney was employed by Evolution Marketing Research (“Evolution”), a private consulting company that contracted its services out to many publicly traded companies, including the pharmaceutical giant Merck. Evolution terminated Gibney’s employment after he reported to his supervisor that Evolution was fraudulently overbilling Merck for its services. Gibney brought a SOX claim, and the district court held that even though Gibney was a protected employee and had reported securities fraud, SOX did not apply because it protects only disclosures aimed at preventing fraud perpetrated by, rather than against, publicly traded companies. Id. at 747–48. The court expressed concern that permitting Gibney’s claim to proceed would transform SOX into a general retaliation statute that would apply to any private company that transacts business with a public company. While Lawson will probably generate an increase in SOX claims, Gibney suggests that courts will likely adopt limiting principles that narrow the scope of SOX coverage for employees of contractors and subcontractors of public companies.

Thereafter, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of New York held, consistent with Gibney, that SOX does not protect employees of contractors whose disclosures concern only the contractors’ violations of federal securities laws. See Anthony v. Nw. Mut. Life Ins. Co., 130 F. Supp. 3d 644 (N.D.N.Y. 2015). That is, “[a] private company’s fraudulent practices do not become subject to § 1514A merely because that company incidentally has a contract with a public company.” Id. at 652. The court enunciated two limitations on the scope of SOX whistleblower protection:

First, the whistleblowing must relate to the contractor’s provision of services to the public company. Thus, § 1514A only covers contractors insofar as they are firsthand witnesses to corporate fraud at a public company—for example, the lawyers and accountants in the Enron scandal who facilitated and contributed to the fraud. It does not cover contractor employees who experience retaliation that is unrelated to the provision of services to a public company. The second limitation is that § 1514A is concerned with public company fraud, whether committed by the public company itself or through its contractors. . . . The effect of these limitations is to restrict § 1514A to situations where a contractor employee is functionally acting as an employee of a public company, and in that capacity, is a witness to fraud by the public company. Id. (citations omitted).

A ruling by a U.S. district court in Wisconsin clarified that, for § 1514A to apply, an actual employment relationship must exist between the plaintiff and the alleged retaliator. See Bogenschneider v. Kimberly Clark Glob. Sales, LLC, 2015 WL 796672 (W.D. Wis. Feb. 25, 2015). Bret Bogenschneider, a former employee of Kimberly Clark, claimed that both Kimberly Clark and its law firm, Godfrey & Kahn, had retaliated against him after he reported alleged tax fraud by Kimberly Clark. Citing Lawson, Bogenschneider argued that Godfrey & Kahn was an “agent” of Kimberly Clark and so could be held liable under § 1514A for retaliation. The district court rejected this argument and dismissed the claim against the law firm, stating:

Although the Court [in Lawson] listed “law firms” in its question, this was in the context of an employee of the law firm, so Lawson does not help plaintiff. . . . Regardless whether Godfrey & Kahn may have participated in any of the alleged retaliation, the law firm is not covered by § 1514A because the firm was not plaintiff’s employer.

Id. at *6.

A September 2018 SDNY decision in Baskett v. Autonomous Research LLP, 2018 WL 4757962 summarizes how courts have applied Lawson:

Since Lawson, federal courts that have addressed the scope of § 806’s “contractor” provision have found that it does not cover situations where the plaintiff employee does not allege fraud related to or engaged in by a public company. In other words, the contractor provision does not apply where a public company has no involvement in the conduct Congress sought to curtail by passing SOX. For instance, in Gibney v. Evolution Marketing Research, LLC, an employee sued his former employer, a private contractor of a public company, after the employer allegedly fired him for complaining that the employer was overbilling a publicly traded company for which it provided marketing services. 25 F. Supp. 3d 741, 742 (E.D. Pa. 2014). The court held that the allegations failed to state a claim, concluding that plaintiff was “advocat[ing] for an impermissibly broad definition of SOX protection that was neither intended by Congress nor contemplated by the Supreme Court in Lawson.” Id. at 747 (noting that the case “does not implicate the peculiar structure of the mutual fund industry” and that denying plaintiff coverage would not “ ‘insulate’ an entire industry from § 1514A protection”). In particular, the court found that “[n]othing in the text of § 1514A or the Lawson decision suggests that SOX was intended to encompass every situation in which any party takes an action that has some attenuated, negative effect on the revenue of a publicly-traded company, and by extension decreases the value of a shareholder’s investment.” Id. at 747–48 (“Plaintiff has not alleged that he blew the whistle on fraud committed by Merck (either acting on its own or acting through contractors like [defendant] ). Rather, [p]laintiff is alleging that [defendant] committed fraud against Merck. Thus, based on Plaintiff’s allegations, Merck is the victim of fraud rather than its perpetrator.”). Numerous other courts have reached similar conclusions. See, e.g., Brown v. Colonial Sav. F.A., No. 4:16-CV-884-A, 2017 WL 1080937, at *4 (N.D. Tex. Mar. 21, 2017) (relying on Lawson and Gibney and concluding that “Plaintiff’s allegations of fraud are too far removed from potentially harming the shareholders of a public company to be covered under § 1514A”); Reyher v. Grant Thornton, LLP, 262 F. Supp. 3d 209, 217 (E.D. Pa. 2017) (dismissing SOX claim, finding that the “purported whistleblower employed by a private company cannot invoke the protections of section 1514A simply because her employer happens to contract with public companies on matters unrelated to the alleged whistleblowing”); Anthony v. Nw. Mut. Life Ins. Co., 130 F. Supp. 3d 644, 652 (N.D.N.Y. 2015) (finding that “§ 1514A only covers contractors insofar as they are firsthand witnesses to corporate fraud at a public company”).

A recent ALJ decision in Kolehmainen v. CS Auto HND, LLC, 2020–SOX–00044 (ALJ March 30, 2022) surveys decisions applying the limiting principles set forth in Lawson.

Whistleblower Lawyers Representing Sarbanes-Oxley Whistleblowers

We have assembled a team of leading SOX whistleblower protection lawyers to provide top-notch representation to Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) whistleblowers. Recently Washingtonian magazine named two of our attorneys top whistleblower lawyers.

U.S. News and Best Lawyers® have named Zuckerman Law a Tier 1 Law Firm in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area.

The SOX whistleblower lawyers at Zuckerman Law have substantial experience litigating Sarbanes Oxley whistleblower retaliation claims and have achieved substantial recoveries for officers, executives, accountants, auditors, and other senior professionals.

To schedule a free preliminary consultation, click here or call us at 202-262-8959.